Europe is conventionally a continent: most atlases place its boundary along the Ural Mountains and Ural River, the Caspian Sea, the Greater Caucasus watershed, and the Turkish Straits. Geologically, however, Europe is not a separate tectonic plate; it sits on the Eurasian Plate. So the “continent” label is historical–geographic, not tectonic.

The Short Answer (and Why It’s Tricky)

Yes, Europe is a continent in the seven-continent model used across the English-speaking world. This model lists Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia. It is the framing used by many educators and by reference works such as National Geographic’s “Continent” definition and Encyclopædia Britannica’s “Europe”.

But “continent” is not a strict law of nature; it is a human classification that blends physical geography with history and culture. Geologists map plates (Eurasian, African, Arabian…), not classroom continents. That’s why a geologist can truthfully say Europe is not a separate tectonic continent even while teachers truthfully present Europe as one of the seven world continents. Understanding the criteria behind the label resolves the apparent contradiction.

Geographic (Physiographic) Criteria — Where Europe “Ends”

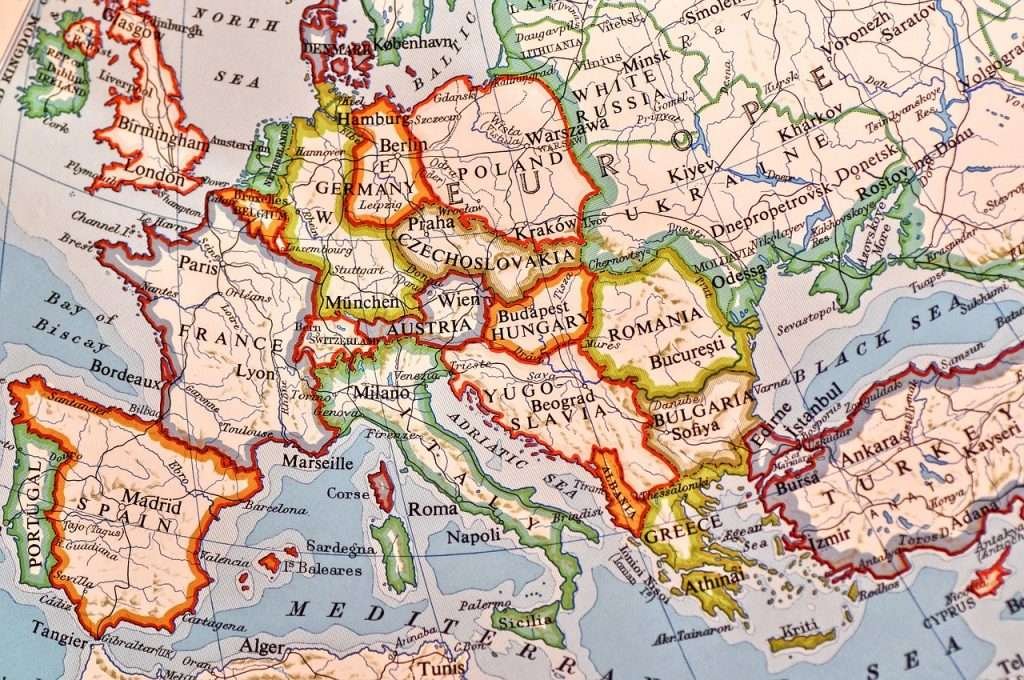

Modern atlases typically draw Europe’s edge along a chain of natural features from northeast to southwest. This line starts at the Ural Mountains—a range about 1,550 miles (2,500 kilometers) long—continues down the Ural River, crosses the Caspian Sea, follows the high crest of the Greater Caucasus, then traverses the Black Sea to the Bosporus–Sea of Marmara–Dardanelles (the Turkish Straits). The city of Istanbul famously straddles the Bosporus, with neighborhoods on both “European” and “Asian” shores. This physiographic line is summarized in leading references such as Britannica and National Geographic.

These boundaries are conventional, not absolute walls. The Urals are low and passable in many places; the Caucasus hosts transcontinental countries; and the Bosporus is only about 19 miles (31 kilometers) long and less than 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) wide at most points. Yet as a package, this chain of features has proven practical and durable for mapmaking, education, and statistics.

Urals → Ural River → Caspian → Caucasus crest → Turkish Straits

This is the mainstream “textbook” route: Urals (Europe/Asia divide), Ural River southward, Caspian Sea, high watershed of the Greater Caucasus, then across the Black Sea and through the Bosporus and Dardanelles to the Aegean. It is the line most readers will see on school maps and in general encyclopedias.

Alternative line via the Kuma–Manych Depression

Some geographers prefer a gentler lowland boundary from the northern Caspian toward the Sea of Azov known as the Kuma–Manych Depression. This alternative shifts the “line” north of the Greater Caucasus, placing all of the Caucasus states (Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan) in Asia rather than splitting them along the mountain crest. Authoritative sources note both versions, but the crest-of-Caucasus line is more common in contemporary atlases.

| Boundary Model | Route (simplified) | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Caucasus Crest (mainstream) | Urals → Ural River → Caspian → Greater Caucasus crest → Black Sea → Bosporus–Dardanelles | Splits the Caucasus across the watershed; Istanbul spans two continents; widely taught in schools and atlases. |

| Kuma–Manych Depression (alternative) | Urals → Emba/Ural lowlands → Caspian → Kuma–Manych lowland → Sea of Azov | Places all of the Greater Caucasus south of Europe; emphasizes a continuous lowland boundary. |

Geologic Criteria — Plates, Cratons, and Why “Continent” ≠ Tectonic Plate

In geology, continents are not counted the way school atlases do. Earth’s outer shell consists of tectonic plates that move slowly. Europe sits on the Eurasian Plate, which also carries most of Asia. The geological map shows plate boundaries—mid-ocean ridges, subduction zones, major faults—rather than the “Europe/Asia” line seen in atlases. For instance, Iceland lies along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where the Eurasian and North American plates diverge.

Because plates do not match our cultural continents, a geologist will say Europe is not a separate tectonic continent. That doesn’t make the geographic term “continent” wrong—it just belongs to a different classification system.

Cultural–Historical Criteria — Why Europe Became a Separate World Region

“Europe” as a concept is older than modern geology. Classical writers separated Europa from Asia and Libya (Africa) long before anyone mapped tectonic plates. Over centuries, shared historical experiences—Roman expansion and collapse, the spread of Christianity, the Renaissance, scientific revolutions, and the modern nation-state—helped cement “Europe” as a distinct world region in education, diplomacy, and culture.

Physical geography reinforced the idea. Europe is often called a “peninsula of peninsulas”—a deeply indented western extension of Eurasia with long coastlines and many sub-regions (Iberian, Italian, Balkan peninsulas; the North European Plain; the Alpine arc). This mixture of seas and varied landforms created distinct cultural spaces that nevertheless interacted intensely.

Political/Statistical & Educational Models — UN M49, UEFA, and 7-vs-6-Continent School Maps

Institutions need consistent groupings. The United Nations Statistics Division (UN M49) divides the world into macro-regions for data analysis. These regions are practical and sometimes differ from school “continents.” For example, the UN places some transcontinental countries in the regions that best serve statistical comparability, not to redefine continents but to standardize reporting.

In sports, UEFA includes countries that are politically and culturally tied to Europe even if they are partly in Asia. In schools, the seven-continent model dominates in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and Australia, while some curricula teach a six-continent world by merging Europe and Asia into Eurasia (or merging North and South America into one “America”). The coexistence of these systems shows that “continent” is a model tailored to purpose—education, statistics, or governance.

Active Debates & Edge Cases — Who’s “Right” and Why the Debates Persist

Why debates? Because each criterion emphasizes something different. Geographers prize coherent natural boundaries (hence the Urals/Caucasus/Staits line). Geologists prioritize plates (which erase the Europe/Asia line). Historians and institutions prioritize cultural and practical groupings (which keep “Europe” as a distinct region). None of these aims are wrong; they answer different questions.

Edge cases: Turkey spans the Bosporus; Istanbul is famously bi-continental. Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan sit along the Caucasus, and their placement shifts depending on whether one uses the Caucasus crest or the Kuma–Manych Depression. Cyprus lies south of Anatolia on the Anatolian micro-plate but is commonly treated as European in cultural and institutional contexts. Iceland straddles the Mid-Atlantic Ridge yet is unquestionably “European” in cultural terms. These cases show why context—physical, geologic, cultural, or institutional—matters when we label a place.

FAQ

So, is Europe a continent or not?

In the mainstream seven-continent model, yes: Europe is a continent with conventional boundaries (Urals, Ural River, Caspian, Caucasus crest, Turkish Straits). In a strict geologic sense, no: it is part of the Eurasian tectonic plate. Both statements are accurate within their systems.

Why do some maps put the Europe–Asia boundary in the Kuma–Manych Depression?

It forms a continuous lowland corridor from the Caspian toward the Sea of Azov. Some geographers prefer lowlands over mountain crests for boundaries. Most modern atlases, however, favor the Greater Caucasus watershed line.

Does the UN officially define continents?

No. The UN’s M49 geoscheme groups countries into regions for statistical purposes. It isn’t a ruling on “true” continents; it’s a consistent coding system for data.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Europe is a continent by geographic convention but not a separate tectonic plate.

- Common boundary: Urals → Ural River → Caspian → Greater Caucasus crest → Bosporus–Dardanelles.

- An alternative boundary uses the Kuma–Manych Depression, shifting the status of Caucasus states.

- Institutions (UN M49, UEFA) group countries for practical reasons that may not mirror school continents.

- Debates persist because “continent” answers different needs: physical mapping, geology, culture, and policy.