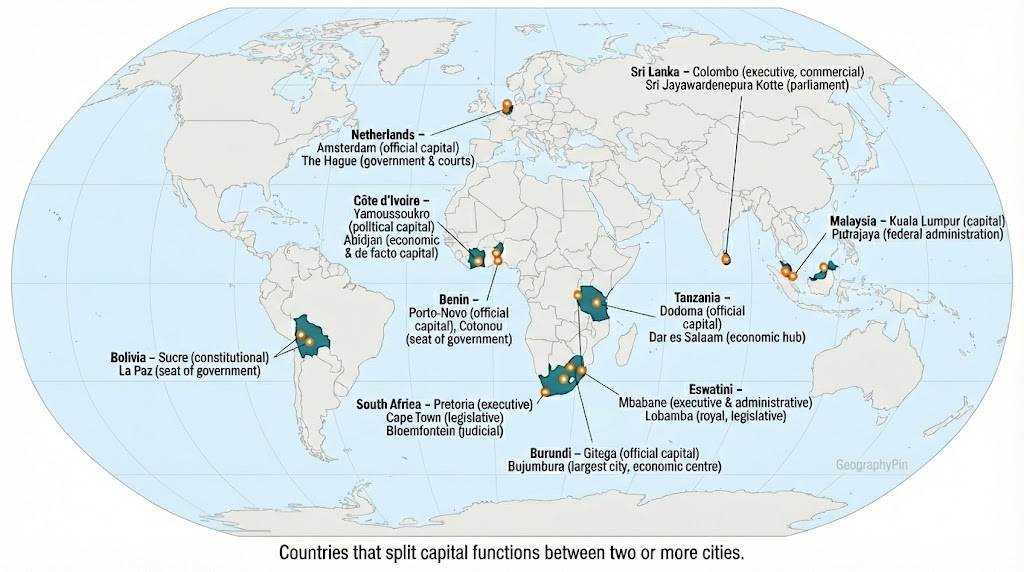

Countries with more than one capital (or multiple capitals) are states that deliberately split core functions like the parliament, president or highest courts between two or more cities instead of just one. As of 2025, only a small group – including South Africa, Bolivia, the Netherlands, Sri Lanka, Eswatini, Malaysia and Tanzania – uses this model to balance history, regional power and practical needs.

What Actually Counts as a “Capital City”?

At first glance, “capital city” sounds simple: the main city where a country is run from. In reality, the label hides several different roles. Some cities are written into the constitution as the official capital. Others host the president, cabinet and ministries. In some countries, the parliament or the supreme court sits somewhere else again.

On top of that, there is a big gap between law and practice. A constitution might name one capital, but the real seat of government – the place where ministers work every day – can sit in a different city. This is why lists of “countries with more than one capital” sometimes disagree. Some count only cities named in the constitution, while others also include de facto capitals that host the government, courts or monarch. In short, a country can have a de jure capital (on paper in the constitution) and a de facto capital (where power actually sits day to day), and multi-capital systems often mix the two.

- De jure capital: the city named in the constitution as the capital.

- De facto capital: the city where the government actually works day to day.

Constitutional, Administrative, Legislative and Judicial Capitals

To understand multi-capital systems, it helps to split capital roles into four broad types:

- Constitutional capital: the city named in a country’s constitution or basic law as the capital, even if many offices work elsewhere (for example, Sucre in Bolivia and Amsterdam in the Netherlands).

- Administrative or executive capital: the seat of government where the head of state, head of government and ministries are based day to day (La Paz, Pretoria, The Hague, Putrajaya).

- Legislative capital: the city that hosts the national parliament or main legislative body (Cape Town, Lobamba, Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte, Valparaíso).

- Judicial capital: the seat of the supreme or constitutional court (Bloemfontein, Sucre in Bolivia, and similar locations in other states).

Some cities also serve as economic or commercial capitals, housing the biggest stock exchange, port or airport – think of Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire or Dar es Salaam in Tanzania – without always being the official political capital.

| Capital type in multi-capital countries (as of 2025) | Typical role & example |

|---|---|

| Constitutional capital | Named in the constitution as the capital (Sucre in Bolivia; Amsterdam in the Netherlands). |

| Administrative / executive capital | Seat of government and ministries (Pretoria in South Africa; La Paz in Bolivia; Putrajaya in Malaysia). |

| Legislative capital | Where the national parliament meets (Cape Town in South Africa; Lobamba in Eswatini; Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte in Sri Lanka). |

| Judicial capital | Seat of the highest courts (Bloemfontein for South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal; Sucre for Bolivia’s judiciary). |

| Economic / commercial capital | Main financial or port city, often still hosting some government functions (Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire; Dar es Salaam in Tanzania; Colombo in Sri Lanka). |

Why Some Countries Choose Multiple Capitals

So why not keep everything in one place, like Washington, D.C. or London? For multi-capital countries, the answer usually lies in geography, history and domestic politics. Splitting capital functions can calm regional tensions, balance old rivalries or support new development plans away from a crowded main city.

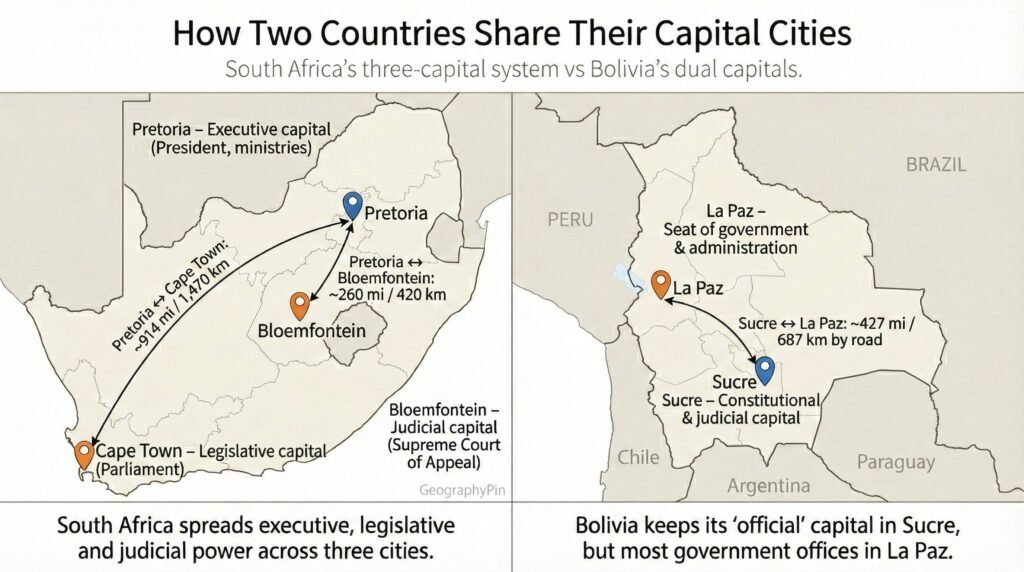

In other cases, the choice is a compromise after conflict or colonisation. Bolivia is the classic Sucre vs La Paz capital compromise, with one city official and the other the de facto seat of government. South Africa’s three-capital system reflects a bargain between formerly separate colonies and republics coming together in 1910. These arrangements are political deals written into geography.

Spreading Power and Jobs

One clear motive is to avoid putting all political weight into a single city. By putting the parliament in one place, the president and ministries in another, and sometimes the courts somewhere else, governments can signal that no single region “owns” the state. This is particularly attractive in diverse countries with strong regional identities.

There is also an economic angle. Moving ministries, universities and agencies into a second or third capital brings public sector jobs, infrastructure and services. South Africa’s three capitals, Tanzania’s move to Dodoma, and Malaysia’s creation of Putrajaya all aimed, in different ways, to push development away from older coastal or colonial centres into newer planned cities.

Historical Compromises After Conflict or Colonisation

Multi-capital setups also freeze fragile peace deals into the map. After long debates in Bolivia, Sucre kept its symbolic status as the historical capital, while La Paz kept the growing government apparatus. In South Africa, the former Boer republics and British colonies each gained part of the new Union’s political system through Pretoria, Cape Town and Bloemfontein, which people now quote in “why South Africa has three capitals” explainers.

Elsewhere, colonial legacies and urban overcrowding pushed leaders to build or promote fresh capitals without completely downgrading existing ones. Côte d’Ivoire’s Yamoussoukro was promoted as the official capital in 1983, but Abidjan remains the main economic and, in practice, political centre. Similar logics appear in Benin (Porto-Novo vs Cotonou) and Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur vs Putrajaya).

Security and Geography

In a few cases, geography and security also push leaders to split or move capital functions. Shifting some institutions inland can reduce exposure to coastal attacks, border tensions or natural hazards like tsunamis and storm surges. That logic sits behind several “new capital” projects worldwide and helps explain why some states keep one capital near the coast while promoting another further inland, even if they don’t always fully complete the move.

List of Countries With More Than One Capital (Quick Table)

There is no absolutely fixed list of “countries with more than one capital”. Some sources count only those where two or more capitals are formally recognised in law; others include countries where the official capital and the day-to-day seat of government are different cities.

This table focuses on countries where capital functions are deliberately split between two or more cities on a long-term basis. It includes cases where one city is the official or constitutional capital and another is the de facto seat of government, but it leaves out short-term wartime capitals or future planned capitals that are not yet fully in use. Borderline examples, such as Chile (Santiago vs Valparaíso), the Czech Republic (Prague vs Brno as judicial seat), Indonesia (Jakarta vs the planned Nusantara) and conflict-affected Yemen, are noted separately rather than treated as stable multi-capital systems.

Which countries have more than one capital as of 2025?

Most sources agree on around nine to ten core cases of countries with more than one capital as of 2025. These include South Africa, Bolivia, the Netherlands, Sri Lanka, Eswatini, Malaysia, Tanzania, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin and Burundi. A few other states sometimes appear on wider lists, but they usually involve temporary wartime capitals or partial capital moves that are still in progress.

| Country | Capital city / role | Second (or third) capital / role | Notes (as of 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

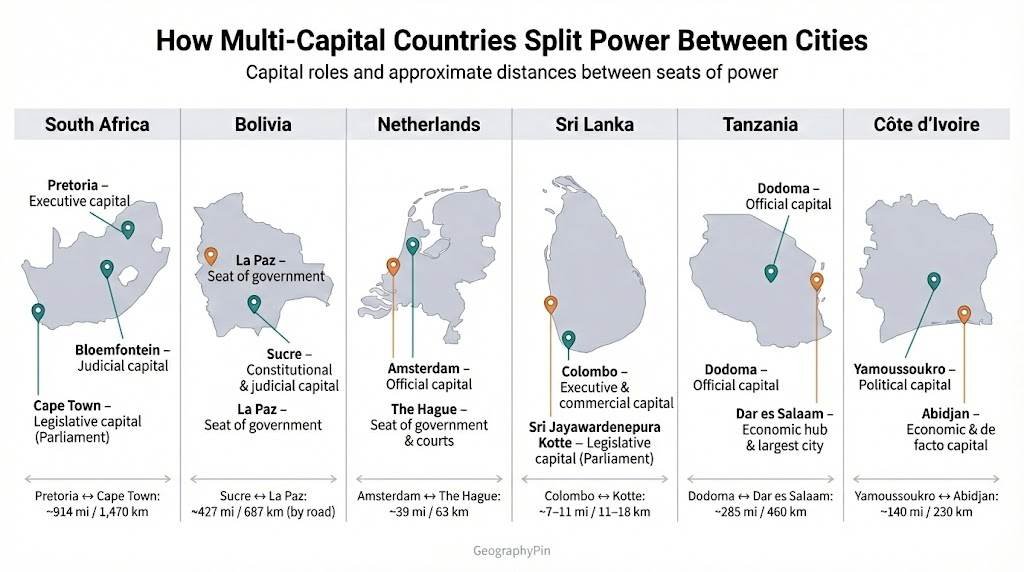

| South Africa | Pretoria – administrative and executive capital | Cape Town – legislative capital (parliament); Bloemfontein – judicial capital | Three separate cities share branches of government, with Pretoria and Cape Town separated by a long journey across the country. |

| Bolivia | Sucre – constitutional and judicial capital | La Paz – de facto seat of government and legislature | The Sucre vs La Paz capital debate produced a compromise: Sucre kept symbolic and judicial roles, while La Paz holds the government and parliament. |

| Netherlands | Amsterdam – constitutional and royal capital | The Hague – seat of government, parliament, many embassies and international courts | Amsterdam vs The Hague as capitals is a classic example of an official capital and a political capital coexisting in one small country. |

| Sri Lanka | Colombo – commercial, executive and judicial capital | Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte – legislative and administrative capital (parliament complex) | The two cities sit in the same metro area, roughly 7–11 miles (about 11–18 kilometers) apart depending on the route. |

| Eswatini | Mbabane – administrative capital and seat of government | Lobamba – legislative and royal capital | Parliament sits in Lobamba, while ministries operate mainly from Mbabane. |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Yamoussoukro – official political capital | Abidjan – de facto administrative and economic capital | Yamoussoukro vs Abidjan is a long-running split: the inland city is the official capital, but Abidjan remains the main economic and practical political centre. |

| Benin | Porto-Novo – official capital | Cotonou – de facto seat of government and main economic centre | Ministries and embassies mostly operate from Cotonou, the port city on the Gulf of Guinea. |

| Malaysia | Kuala Lumpur – constitutional capital, parliament and royal palace | Putrajaya – planned administrative capital and main government hub | Government ministries moved to Putrajaya to ease congestion in Kuala Lumpur and create a modern administrative city. |

| Tanzania | Dodoma – official national capital, increasingly hosting state functions | Dar es Salaam – main commercial city and long-time seat of many ministries and embassies | Dodoma was designated the capital in the 1970s and has gradually taken over many state functions, while the Dodoma vs Dar es Salaam split still matters in politics and business. |

| Burundi | Gitega – official political capital | Bujumbura – economic and former political capital | The capital moved inland to Gitega in 2019, while Bujumbura remains the biggest city and economic hub. |

A few other states, such as Chile (Santiago vs Valparaíso), or conflict-affected countries like Yemen and Afghanistan, sometimes appear on broader lists because their legislature or wartime seat of government sits in a different city from the official capital. In this article, they are treated as borderline or temporary cases rather than stable multi-capital systems, so they are not included in the main table.

Key Case Studies: How Multi-Capital Systems Work

This guide answers common questions such as “which countries have more than one capital?”, “why does South Africa have three capitals?” and how official capitals differ from de facto seats of government. The case studies below show how those abstract rules play out on the ground.

South Africa – Three Capitals for Three Branches

South Africa is the most famous example people cite when they ask why a country would have three capitals. Pretoria in Gauteng acts as the administrative and executive capital, hosting the president’s offices and most national departments. Cape Town in the Western Cape is the legislative capital where Parliament meets, and Bloemfontein in the Free State is home to key courts and is often described as the judicial capital.

This setup grew out of the 1910 formation of the Union of South Africa, which merged several British colonies and Boer republics. Splitting the branches allowed each region to keep an important function. In practical terms, however, it means officials and members of parliament regularly travel the roughly 914-mile (1,470-kilometer) road journey between Pretoria and Cape Town, or fly the approximately 812-mile (1,307-kilometer) straight-line distance between the two.

Bolivia – Sucre vs La Paz

Bolivia is the classic Sucre vs La Paz capital compromise, with one city official and the other the de facto seat of government. Sucre, named in the constitution, is the historical and judicial capital. It keeps the Supreme Court and much of the country’s early republican symbolism.

La Paz, high in the Andes, is the de facto capital where the president, parliament and ministries are based. The two cities are separated by around 258 miles (415 kilometers) as the crow flies and roughly 427 miles (about 687 kilometers) by road, which makes shuttling between them a serious trip.

Netherlands – Amsterdam vs The Hague

In the Netherlands, Amsterdam is the constitutional and royal capital. Kings and queens are inaugurated there, and the city is the country’s largest cultural and economic centre. The Dutch constitution names Amsterdam as the capital city.

Yet the everyday machinery of government operates from The Hague, about 39 miles (63 kilometers) away by road. Parliament, the prime minister’s office, most ministries, and the Supreme Court are there, along with major international bodies like the International Court of Justice. The Amsterdam vs The Hague capitals split is a textbook example of an official capital and a political capital sharing the spotlight in one small, densely populated country.

Sri Lanka and Eswatini – Legislative Capitals Outside the Main City

Sri Lanka and Eswatini show another pattern: moving the legislature to a nearby satellite city while keeping the main economic and executive activity in the older hub. In Sri Lanka, Colombo remains the commercial, executive and judicial centre, but the national parliament sits in a modern complex at Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte, about 7–11 miles (roughly 11–18 kilometers) away in the Colombo metropolitan area.

Eswatini follows a similar logic. Mbabane functions as the administrative capital with ministries and many government offices, while Lobamba holds the parliament and is a royal seat. For both countries, this limited separation helps reduce congestion in the main city while preserving its economic pull.

Tanzania and Côte d’Ivoire – New Capitals, Old Centres

Tanzania and Côte d’Ivoire highlight the challenge of moving a capital away from a dominant coastal city. Tanzania officially shifted its capital from Dar es Salaam to Dodoma for geographic balance and development reasons. Dodoma vs Dar es Salaam remains a live issue, because Dar es Salaam still hosts many diplomatic missions and remains the main port and commercial hub, even as more national institutions relocate inland.

Côte d’Ivoire designated Yamoussoukro, a planned inland city, as its political capital in 1983, but Abidjan continues to function as the country’s largest city, core financial centre and practical seat for many institutions. The Yamoussoukro vs Abidjan split shows how hard it is for a new capital to displace a well-established coastal metropolis. These “half-moves” show that changing a capital is a long process, not a switch that flips overnight.

Do Multiple Capitals Actually Work in Practice?

Multi-capital systems clearly can work – countries like the Netherlands and South Africa have used them for decades – but they come with trade-offs.

On the positive side, splitting power can bring several advantages:

- Reduce resentment in regions that feel overshadowed by a single dominant city.

- Create new centres of growth, as seen in Putrajaya or Dodoma, by moving government jobs away from congested coastal hubs.

- Signal a more balanced or inclusive state structure in countries with strong regional identities.

The downsides start with cost and coordination:

- Officials travel constantly between cities, increasing time and expense.

- Governments must maintain duplicate offices, staff housing and transport links.

- Coordination can be slower when key players are physically separated.

- Critics in poorer countries see the extra costs as wasteful compared with funding services elsewhere.

There is also a symbolic question. A single capital, like Paris or Tokyo, acts as a clear centre of national identity. Multi-capital setups send a more complicated message: unity through diversity and compromise rather than a single city at the top. Whether that feels like strength or weakness depends on local history, politics and how well the system is managed. That mix of higher costs, travel time and coordination headaches is the main reason most countries stick with a single capital, even if it feels unbalanced.

FAQ

How many countries have more than one capital city?

There is no single agreed number, but most recent lists fall in the range of roughly nine to twelve countries with more than one capital as of 2025. The exact count changes depending on whether you include only formal constitutional capitals or also de facto seats of government in places like Tanzania and Côte d’Ivoire.

Why does South Africa have three capitals?

South Africa’s three-capital system reflects a historical compromise from 1910, when the Union of South Africa joined several colonies and republics. Pretoria became the executive capital, Cape Town the legislative capital and Bloemfontein the judicial capital, so each major region gained a piece of the new national state.

Is a commercial capital the same as an official capital?

No. A commercial or economic capital is simply the country’s main business centre. In Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan plays this role, while Yamoussoukro is the official capital. In Tanzania, Dar es Salaam is the main port and economic hub, while Dodoma is the official political capital.

Which countries have capitals very close together, and which are far apart?

In Sri Lanka, Colombo and Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte sit just about 7–11 miles (roughly 11–18 kilometers) apart inside the same metro area. By contrast, Pretoria and Cape Town in South Africa are separated by a long overland journey across the country, so travel between the executive and legislative capitals often involves long flights.

Can a country switch back to having just one capital?

Yes. Multi-capital systems are political choices, not permanent rules. A country could amend its constitution to name a single capital, or gradually move all institutions into one city. In practice, these changes usually take many years because buildings, infrastructure and people are already invested in several places.

Are rival wartime “capitals” the same as planned multi-capital systems?

Not really. In conflict zones, different sides may claim their own “capital”, but these are usually temporary and linked to ongoing war. Planned multi-capital systems, like those in South Africa or the Netherlands, are stable arrangements agreed in law and meant to last.

Why doesn’t every country have more than one capital?

Multi-capital systems can spread power and jobs, but they are expensive and complicated to run. Governments must maintain offices, housing and transport links in several cities, and officials spend a lot of time travelling between them. For many states, it is simpler and cheaper to keep everything concentrated in a single, well-connected capital.

Is The Hague a capital of the Netherlands?

Constitutionally, Amsterdam is the capital of the Netherlands, and royal inaugurations take place there. The Hague, however, is the seat of government: it hosts the parliament, prime minister’s office, most ministries and many embassies. In practice, people sometimes call The Hague the political capital, while Amsterdam remains the official capital.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Only a small group of countries with more than one capital share power across two or more cities, usually for political, historical or geographic reasons.

- “Capital” can mean many things: constitutional, executive, legislative, judicial or commercial roles may sit in different places.

- South Africa, Bolivia and the Netherlands are classic examples of permanent multi-capital systems that often appear in geography exams and news explainers.

- Newer inland capitals like Dodoma and Yamoussoukro show how hard it is to move power away from long-established coastal cities such as Dar es Salaam and Abidjan.

- Multi-capital systems can spread power and jobs but also add cost, travel and complexity to everyday government work, which is why most states still prefer a single capital city.