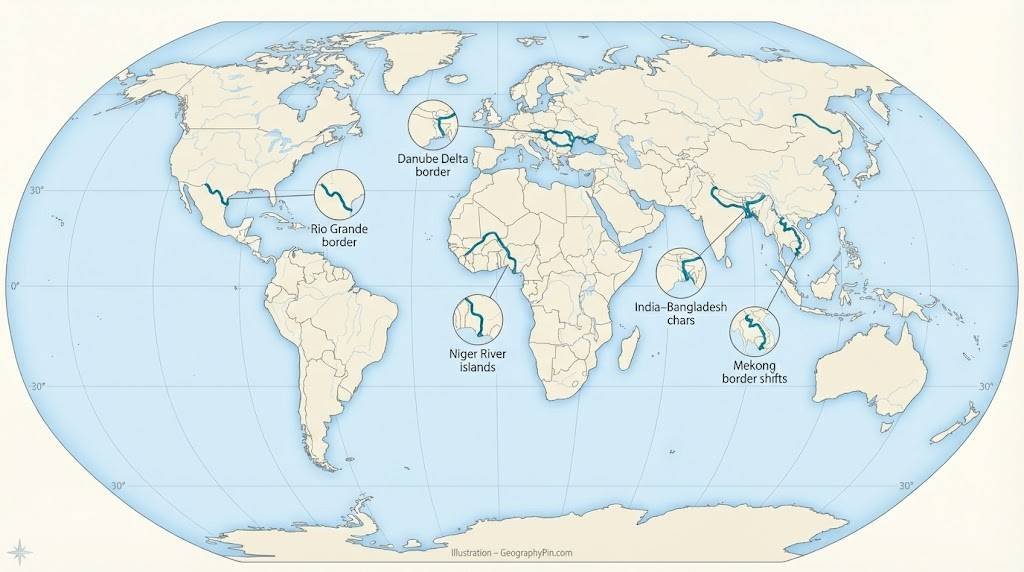

When people talk about “countries whose borders change every year” because of rivers, they mean states whose frontiers follow mobile river channels or deltas. As banks erode, channels shift and new islands appear, the agreed mid-river line can slide, quietly moving tiny pieces of land from one side to the other.

How River Borders Work – Thalweg, Accretion and Moving Lines

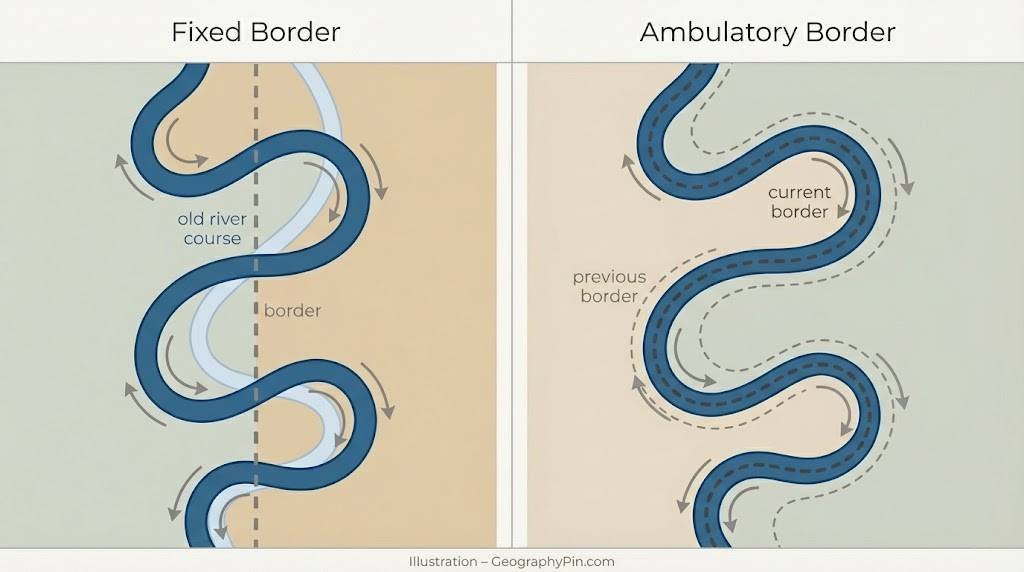

Many river borders are defined by the mid-channel line or the thalweg, the deepest navigable part of the channel. When a river slowly erodes one bank and deposits sediment on the other, that line can drift sideways over time. In law, people call this slow natural process accretion. When a border follows these natural shifts, it becomes an “ambulatory” boundary, a line that can move with the river over time. A sudden jump in the channel after a big flood or an artificial cut is called avulsion. In many treaties, avulsion does not move the legal border even if the water itself rushes into a new course. That distinction—slow-and-natural versus sudden or human-made—explains why some river borders creep gradually. Others stay essentially frozen, even though the river keeps changing.

Core Rules in One Glance

In short, most river borders rely on three ideas: the thalweg, slow accretion that can move the line, and avulsion that usually does not. The table below sums up how these rules play out along different rivers.

| Concept / River | How It Affects the Border |

|---|---|

| Thalweg rule | Border follows the deepest channel; if that channel drifts gradually, the border can shift year by year. |

| Accretion | Slow erosion and deposition move banks and the mid-channel line; many treaties let the border track these natural changes. |

| Avulsion (sudden jumps) | Sudden channel jumps after major floods or artificial cuts usually do not move the legal border, even if the river does. |

| India–Bangladesh chars | New sandbar islands rise and erode in a huge delta; the border must be re-surveyed as channels and chars move. |

| Rio Grande, USA–Mexico | Historic disputes from floods led to a 1970 treaty; much of the border is now fixed by coordinates and engineered channels. |

| Niger and Danube deltas | Branch switching and new islands mean states must agree which channel counts as the main border line at each stage. |

| River / Delta | Countries | Type of Movement | Legal Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna delta | India–Bangladesh | Chars (sandbar islands), braided channels, monsoon-driven shifts | Largely ambulatory; border follows mid-channel lines monitored by joint commissions. |

| Rio Grande | United States–Mexico | Bank erosion, past flood cuts, engineered meanders | Mostly fixed since 1970; river changes no longer move the border automatically. |

| Niger River (middle reach) | Benin–Niger–Nigeria | Shifting islands and multi-channel splits | ICJ judgment fixed principles; some segments remain genuinely ambulatory. |

| Mekong River | Thailand–Laos, Cambodia–Vietnam | Bank erosion, side-channel cutting, reduced sediment | Mixture of thalweg-based borders and locally fixed segments; frequent micro-adjustments. |

| Danube Delta | Romania–Ukraine | Branch switching, new mouth bars, coastal shifts | Border follows agreed channels; small physical shifts handled through joint management. |

India–Bangladesh: Chars in the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna Delta

A Delta That Never Stands Still

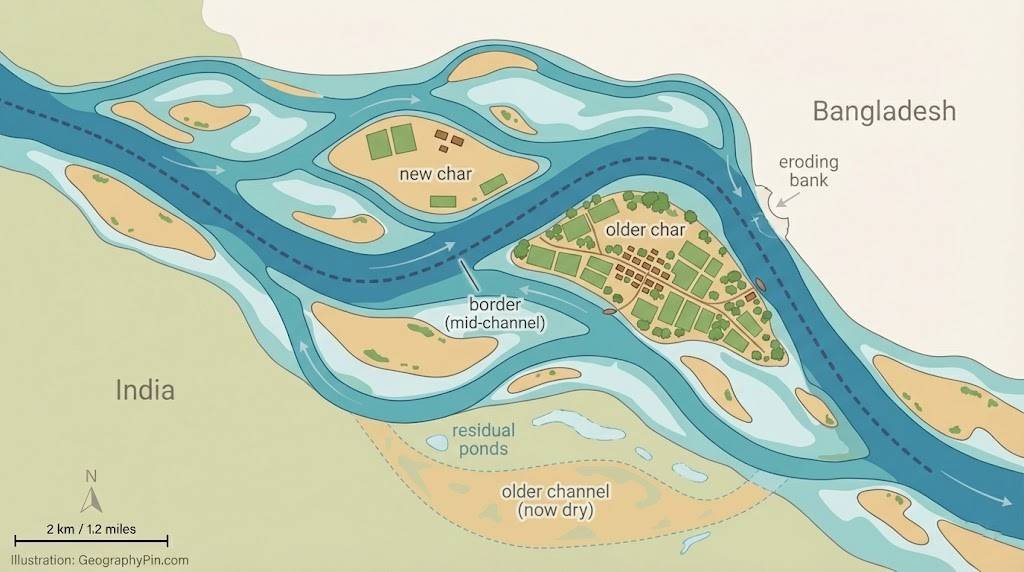

Few places on Earth show moving river borders as clearly as the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna delta shared by India and Bangladesh. This vast lowland covers tens of thousands of square miles (tens of thousands of square kilometers) and hosts around 150 million people. The main rivers braid, split and rejoin, constantly reshaping the delta surface. In this restless setting, sandbar islands known as chars can rise above the water in one monsoon season and shrink or vanish within a decade. These chars are built from Himalayan sediment carried downstream by strong currents.

Some chars grow large enough for whole villages, with homes, rice fields and markets. Many lie close to the international border, especially along the Jamuna, the main Brahmaputra channel, and the lower Meghna. When a char appears mid-channel, whether it falls on one side of the frontier or the other depends on how both countries interpret the thalweg and past survey lines. As the channel deepens or shallows, the mid-channel line can migrate, so the exact border here is a living measurement, not a once-and-for-all drawing. For deeper background, you could link this to a future explainer on the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna delta.

Life on the Chars and a Moving Border

Char communities live with constant uncertainty. A family may invest in a new house and fields only to see a big flood slice the char in two or send it downstream. When chars sit very close to the river border, people can find that, on paper, officials now treat them as residents of the other country. They have not moved a step. That shift affects voter lists, land titles, access to schools and how quickly disaster relief arrives after cyclones or floods.

The 2015 India–Bangladesh Land Boundary Agreement removed complicated enclaves on land, but it did not stop the rivers from wandering. Joint commissions now use satellite images and GPS to watch new channels and islands. Yet the basic reality remains: the border in this delta is an ambulatory line in a moving landscape.

United States–Mexico: The Shifting Rio Grande

From a Shifting River to a Fixed Line

The border between the United States and Mexico follows the Rio Grande for roughly 1,200 miles (about 1,930 kilometers) from El Paso–Ciudad Juárez to the Gulf of Mexico. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and later agreements placed the border along the mid-channel line. In the 19th century, repeated floods near El Paso pushed the river southwards by hundreds of yards/meters. They left former Mexican land on the U.S. side of the water. That change sparked the famous Chamizal dispute. For generations, farmers and residents in this zone saw the river creeping away from their homes while official maps lagged behind.

The Chamizal case was finally settled in the 1960s, and a 1970 boundary treaty gave both countries a more stable framework. The treaty allowed river straightening, concrete banks and diversion channels. It also set fixed coordinates for the political border so that future river shifts would not automatically move the line. An internal link from this section to a future article on the Chamizal dispute and the Rio Grande border would fit naturally. Today, the Rio Grande still erodes banks and lays down sandbars, especially during big rain years. However, much of the border has been “de-rivered” in legal terms. Instead of a pure thalweg rule, the line is tied to agreed coordinates and monuments managed by the International Boundary and Water Commission. Smaller natural shifts can still change how local communities experience the border. For example, a sandbar might block a former crossing point. Even so, the days of major territory swaps caused by single floods are mostly in the past.

West Africa: Niger River Islands Between Benin, Niger and Nigeria

A Court-Defined but Moving Line

On the Niger River in West Africa, multiple channels weave around islands and sandbars, especially between Benin and Niger. Here the question is not just where along the river the border runs, but which of several channels counts as the main one. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) had to answer this in a 2005 case involving the frontier between Benin and Niger and the status of islands such as Lété. The court looked at colonial-era maps, early survey notes and effective control on the ground to decide which branch of the Niger should define the border. It confirmed that, in some stretches, the border follows the mid-channel line of the principal arm and that gradual accretion can still nudge that line over time. That ruling means the Niger here remains a genuinely moving border, even though the legal principles are now clearer.

Downstream, where the Niger marks or crosses the boundary between Niger and Nigeria, seasonal floods can shift sandbanks by tens or hundreds of yards/meters. For herders and fishers, access to river islands can be more important than the exact border line. When an island changes hands on paper, it can affect which side issues fishing licences, grazing permits or policing patrols. The Niger case shows that even when courts give a precise answer, the lived reality of a river border stays fluid.

Mainland Southeast Asia: Mekong River Shifts Along Thailand–Laos and Cambodia–Vietnam

Eroding Banks and Displaced Villages

The Mekong River runs about 2,700 miles (around 4,350 kilometers) from the Tibetan Plateau to the South China Sea. Along parts of the Thailand–Laos border, the international line lies either in the mid-channel or along agreed thalweg segments. Riverbank erosion has eaten into farmland and even forced some villages to relocate houses further inland as the river cuts closer each year. Where the border follows the channel, this can leave people feeling like “their” land has slid toward the other side of the river.

Dams, Sand Mining and Local Disputes

Farther downstream in Cambodia and Vietnam, long-term studies show that the river has, in places, retreated by more than 0.6 miles (about 1 kilometer) sideways in a few decades. At the same time, dams and sand mining have greatly reduced the amount of sediment reaching the Mekong Delta. Less sediment means less natural rebuilding of eroded banks, so the river deepens and undercuts its own margins. Local reports tell of farmers losing orchards to sudden collapse. They also describe riverside paths that once lay safely inland now sitting at the very edge of steep banks.

On stretches where the international border follows the Mekong’s mid-channel line, these changes can fuel local disputes. A bank that used to be clearly on one country’s side may later be guarded by a fence from the other side or cleared by its authorities after a channel shift. Border posts that were once far from the river can end up uncomfortably close. Linking this discussion to a future piece on the Mekong Delta and sand mining would help readers connect the physical and political stories.

Europe: Danube Delta Migrations on the Romania–Ukraine Border

A Delta of Changing Channels

The Danube Delta, shared by Romania and Ukraine, covers about 2,830 square miles (around 7,322 square kilometers). It is a maze of channels, reed beds and lagoons that constantly reworks its own shape. The main Chilia arm, which carries most of the Danube’s flow, also carries the border. Over the past century, people have straightened some channels and built embankments, while natural processes have formed new mouth bars and islands at the river’s entrance to the Black Sea. Since the mid-20th century, upstream dams and flow regulation have reduced sediment delivery to the delta. Some sectors of the coastline now erode, while others still build out slowly. When a channel deepens, it may capture more flow and become the new main route to the sea. That change can alter currents, fishing grounds and navigation patterns along the border. An internal link to a dedicated profile of the Danube Delta would anchor this section in your wider river and sea coverage.

War-Time Traffic and Local Lives

Human impacts have intensified since the start of the full-scale war in Ukraine in 2022. Shipping traffic for grain exports on some Chilia reaches has multiplied, bringing more wake erosion, noise and safety risks for small boats. Fishers in border villages have had to adapt to rerouted shipping lanes and occasionally stricter patrols. Some farmers near eroding banks now face the question of which authority they should approach for permits and compensation when land slips away. On paper the border is still defined by agreed channels and coordinates, but for people living there the “working border” is whatever stretch of water is busy with guards, ships and changing banks in any given season.

Do These Borders Really Change Every Year?

Physical Change vs Legal Change

In purely physical terms, yes. In deltas like the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna or the Danube, and along parts of the Mekong and Niger, channels and sandbars shift almost every flood season. New islands appear, banks erode, and the mid-channel line can drift by several yards or tens of yards (a few to a few dozen meters) in a single year. On that level, these countries really do see bits of their territory reshape from one year to the next.

Legally, the picture is more cautious. Some states, such as the USA and Mexico, have chosen to “freeze” their river borders using fixed coordinates, so later river shifts do not move the border automatically. Others keep thalweg or mid-channel definitions but manage them through joint commissions, regular surveys and, when necessary, arbitration or court cases. The result is that physical change may be yearly, while legal change tends to come in slow, negotiated steps rather than constant redrawing of maps.

Climate change is now amplifying many of these processes. Stronger floods, shifting monsoon patterns and sea-level rise in low-lying deltas can speed up bank erosion and drown islands faster. Upstream dams and changing rainfall patterns can reduce sediment loads, making coasts and banks more fragile. That means river-border management in the 21st century has to account not only for the usual dance of meanders and islands, but also for long-term trends that make the dance faster and less predictable.

Other Rivers Where Borders Have Moved With the Water

- Rhine and Meuse (Netherlands–Germany–Belgium) – Once more flexible, now heavily engineered with fixed borders and managed channels.

- Amur (Russia–China) – Islands and channel shifts were the subject of late 20th and early 21st century negotiations, leading to agreed adjustments.

- Tumen River (Russia–China–North Korea) – Small shifts have required local clarifications, though no major modern disputes have escalated.

- Central European rivers – Short stretches of rivers like the Drava or Tisza have seen local border adjustments after floods or engineering projects.

These examples show that moving river borders are not rare accidents, but a recurring challenge wherever politics meets dynamic channels.

FAQ

Which countries see the most frequent river-driven border changes?

India and Bangladesh around the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna chars are often highlighted as the most dynamic example. Other notable cases include parts of the Niger River between Benin and Niger, stretches of the Mekong between Thailand and Laos or Cambodia and Vietnam, and sections of the Danube Delta between Romania and Ukraine.

Do people really change nationality when a river moves?

It can happen in principle, especially on chars in the India–Bangladesh delta or in older cases like the Chamizal dispute on the Rio Grande. Today, countries usually try to avoid surprise nationality changes by fixing legal borders with coordinates and handling river shifts through local agreements rather than automatic transfers of citizenship.

How do countries keep track of moving river borders?

They mix classic tools and modern tech: boundary markers on land, regular patrols, aerial photos, satellite imagery and GPS surveys. Joint boundary commissions compare data, visit problem spots and agree on how to apply rules on accretion and avulsion so that small physical changes do not turn into major diplomatic disputes.

Can climate change make river borders move more?

Yes. Stronger storms and floods can speed up erosion, while sea-level rise can drown low islands and push deltas inland. Changes in rainfall and upstream dams can reduce sediment flows, making banks more fragile. All of this can make river borders more mobile in physical terms and put extra pressure on the treaties and institutions that manage them.

Are there rivers where borders used to move but are now fixed?

Several. The Rio Grande and Colorado between the USA and Mexico, and parts of the Rhine and Meuse in Western Europe, used to rely more strongly on shifting channels. Modern boundary treaties now use fixed coordinates, stabilized channels or artificial cuts so that changes in the river’s course no longer move the border itself.

Who wrote this article and how current is the information?

This article is written by Zurab Koniashvili for GeographyPin.com. It is based on treaties, court cases and scientific research available as of 2025. Where different sources give different numbers, ranges or the most widely accepted values are used, and the focus stays on long-term patterns rather than short-term anomalies.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Some international borders, especially in big river deltas and braided channels, physically shift almost every year as rivers migrate.

- International law draws a line between slow accretion, which can move borders, and sudden avulsion, which usually does not.

- Case studies from India–Bangladesh, the Rio Grande, the Niger, the Mekong and the Danube show different ways states manage moving rivers.

- Modern tools—satellites, GPS, engineering and joint commissions—help keep small physical changes from turning into big political crises.

- Climate change, dams and sand mining are likely to make river-border management even more challenging through the rest of this century.