Is Iceland in North America or Europe? (Plates, Maps & Politics Explained)

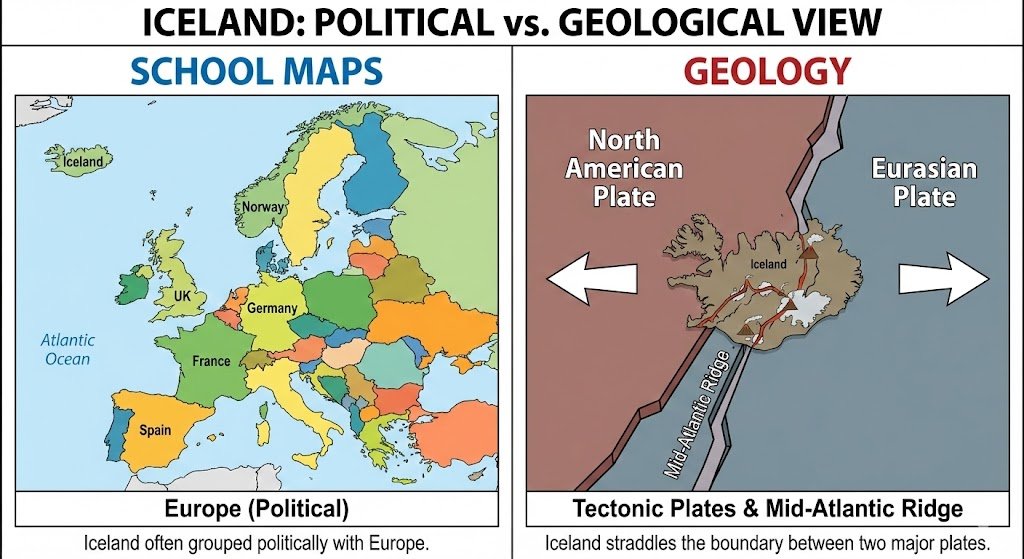

Iceland straddles the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, so its western part stands on the North American tectonic plate and its eastern part on the Eurasian plate. However, in the early 2020s most atlases, institutions and data sets treat Iceland as a European and Nordic country. They group it with Europe in cultural, political and economic terms.

Quick Answer: Geology Says “Both”, Human Geography Says “Europe”

From a physical point of view, Iceland is one of the most unusual countries on Earth. It rises from the floor of the North Atlantic Ocean where two tectonic plates meet and spread apart. The western part of the island sits on the North American plate, while the eastern part rests on the Eurasian plate. The plate boundary actually cuts across the country from southwest to northeast.

Human geography, however, works differently. When governments, schools and international organizations talk about Iceland, they almost always place it in Europe. They describe it as a Nordic island state, closely linked to Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Finland in language, politics and economics. On continent quizzes and in school textbooks, the expected answer to “Which continent is Iceland in?” is Europe, not North America.

So the best short answer is this: geologically Iceland spans the North American and Eurasian plates, but in politics, culture and most practical uses people treat it as a European country. Understanding why requires looking more closely at its location, its history and how geographers define continents and regions in the first place.

Distances and Basic Geography

Iceland has an area of about 39,700 square miles (around 103,000 square kilometers), making it slightly larger than the U.S. state of Kentucky and roughly the same size as South Korea. Its coastline is highly indented, with deep fjords in the west and northwest and long, curving bays in the north. Much of the interior is a high plateau of lava fields, glaciers and barren rock.

The island lies just south of the Arctic Circle, between roughly 63° and 67° north latitude. The closest point to Greenland is about 180 miles (around 290 kilometers) away across the Denmark Strait. The distance to the Scottish mainland is 460–480 miles (740–770 kilometers). Norway’s coast lies about 600 miles (965 kilometers) to the east. These distances place Iceland midway between North America and mainland Europe. However, shipping routes, flights and political ties connect it much more strongly to European ports and airports.

| Aspect | Iceland’s “Identity” |

|---|---|

| Tectonic plates | Straddles Mid-Atlantic Ridge; western regions on North American plate, eastern regions on Eurasian plate. |

| Continent on school maps | Almost always appears colored and labelled as part of Europe. |

| Regional label | Nordic and Northern European country. |

| Population (early 2020s) | Around 380,000–390,000 people, mostly along the coasts. |

| Capital city | Reykjavík, in the southwest, home to roughly one-third of the population. |

| Language | Icelandic, a North Germanic (Nordic) language descended from Old Norse. |

| Time zone | UTC+0 all year, similar to the UK in winter rather than North American time zones. |

| International groupings | Most UN and statistical systems class it with Western and Northern Europe. |

Continents, Plates and Regions: Three Different Systems

A big part of the confusion comes from mixing up three separate ideas: tectonic plates, continents and world regions. Tectonic plates are huge blocks of crust and upper mantle. They carry continents and oceans across the planet’s surface over millions of years. Continents are large landmasses used in school geography, such as Europe, Asia and North America. World regions are flexible groupings used by economists, diplomats and sports associations to organize data and competitions.

These three systems do not always overlap perfectly. For example, the Arabian Peninsula sits on its own tectonic plate, but people still count it as part of Asia. The Indian subcontinent rides on the Indian plate, yet people treat it as part of Asia as well. In the same way, Iceland’s location on an oceanic ridge does not stop people from putting it into the European “box” when drawing regional maps or collecting statistics.

When teachers ask questions like “What continent is Iceland in?”, they are almost always thinking of continents as human-defined regions, not as rigid geologic categories. That is why the expected school answer is Europe. Geology teachers, on the other hand, care about plates, rift zones and magma, and they often stress that Iceland is a special case because it is being pulled apart by the spreading of the North Atlantic Ocean basin.

Iceland on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a chain of underwater mountains running roughly north–south down the center of the Atlantic Ocean. In most places it lies under thousands of feet (hundreds or thousands of meters) of water. Near Iceland, however, volcanic activity and a powerful hot spot have built enough lava and rock to raise the ridge above sea level, forming the island we see today.

In places like Þingvellir National Park, about 30 miles (roughly 50 kilometers) east of Reykjavík, visitors can walk through a rift valley where the ground has pulled apart. Steep cliffs mark the edges of the plates. The western side moves slowly toward North America, while the eastern side shifts toward mainland Europe. Both move at a rate of a few centimeters (about an inch) per year. Frequent small earthquakes and regular volcanic eruptions show that the plates still move and that new crust forms under Iceland all the time.

Politics, Culture and Economy: Why Iceland Is Treated as European

While geology explains the plate story, politics and culture explain why people classify Iceland as European almost everywhere else. Iceland was settled mainly by Norse sailors and farmers from what is now Norway, along with Celtic people from the British Isles, during the late 9th and 10th centuries. Its language, sagas and legal traditions grew out of this northern European heritage and still echo it strongly today.

Modern Iceland is part of the Nordic family of states, along with Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Finland. It belongs to the Nordic Council, which promotes close cooperation on everything from social policy to culture. Economically, Iceland is highly integrated with the rest of Europe. It is a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and participates in the European Economic Area (EEA), which means Icelandic companies have access to the European Union’s single market in goods, services, capital and people.

Iceland is also part of the Schengen Area. For most travelers this means that once you pass passport control on entering Iceland from another Schengen country, you can move between Iceland and most of mainland Europe without additional border checks. Iceland issues its own currency, the Icelandic króna, but trade statistics and economic reports group it with Western and Northern Europe.

In security and diplomacy, Iceland belongs to the Western camp. It is a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and plays a key role in the sea and air gap between Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom. In the United Nations, Iceland falls under the Western European and Others Group (WEOG), which confirms again how the country is aligned. All of this means that when analysts speak about “European energy security”, “Nordic welfare states” or “European Arctic policy”, Iceland is part of the conversation.

Timeline: Iceland’s Integration with European Institutions

A short timeline helps show how Iceland’s political and economic ties have grown inside the European family over the last century. Years are rounded to keep the big picture clear.

| Year (approx.) | Event and European Link |

|---|---|

| 1918–1944 | Iceland becomes a sovereign kingdom in personal union with Denmark, then later declares itself a republic during World War II. |

| 1949 | Joins NATO, linking its security directly to North American and Western European allies. |

| 1952 | Becomes a founding member of the Nordic Council, deepening ties with other Nordic countries. |

| 1970 | Joins the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), gaining better access to Western European markets. |

| 1990s | Signs the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement and enters the Schengen Area, aligning closely with the European Union’s internal market and border rules. |

| 2009–2015 | Opens EU accession talks after the global financial crisis, then later suspends and withdraws the application, while staying in EFTA and EEA. |

| Early 2020s | Debates continue about whether to deepen ties with EU institutions, but no serious move toward North American regional blocs appears. |

How Maps, Atlases and Data Sets Place Iceland

Iceland in Atlases and School Maps

If you open a modern world atlas or school wall map, Iceland almost always appears in the chapter or section on Europe. Publishers usually shade it the same color as other European countries, sometimes with a small inset map that shows the North Atlantic more clearly. In children’s books many authors label it “Europe’s westernmost country” or “a Nordic island in the North Atlantic”.

Iceland in Statistics and Everyday Media

International organizations follow a similar pattern. The United Nations geoscheme, for example, groups Iceland under “Northern Europe” along with Scandinavia, the Baltic states, Ireland and the United Kingdom. Many statistical agencies use categories like “Western Europe” or “Nordic region”, and they count Iceland there. Sports bodies also place Iceland in Europe: its national football (soccer) team, for instance, competes under UEFA, not under a North or Central American confederation.

Digital platforms copy these conventions. Travel websites list Iceland in their “Europe trips” section. Airline booking engines treat flights from Reykjavík to London, Copenhagen or Berlin as short- to medium-haul European routes, while flights to New York or Toronto are sold as transatlantic crossings. Even in weather apps, Iceland appears on the European forecast page more often than on North American screens. All of this builds a mental map in which Iceland belongs firmly to Europe, even for people who have never heard of tectonic plates.

Why the Answer Matters

At first, the question “Is Iceland in North America or Europe?” might sound like a trivia challenge. In reality it helps students and travelers think more carefully about how humans divide up the world. It shows that the lines we draw on maps serve different purposes: some are based on rock and crust, others on language and history, and still others on trade, law or sport.

For Students and Educators

For students, Iceland is a helpful example to test definitions. If a teacher defines a continent only as a large continuous landmass, then Iceland is technically an oceanic island, not on any continent. If the teacher defines continents more broadly as regions of the world, Iceland fits Europe because of its Nordic culture and political ties. Explaining this clearly can raise the level of a geography project or classroom presentation.

For Policy and Science

For policymakers and scientists, Iceland also has a strategic importance that goes beyond labels. It stands at the center of the North Atlantic sea lanes, sits within the Arctic region and hosts important monitoring stations for ocean currents, weather and volcanic ash. Decisions about airspace, shipping routes or Arctic environmental protection often bring North American and European actors together in Reykjavík. Understanding Iceland’s “in-between” position helps explain why so many international meetings and exercises take place there.

FAQ

For a school test, should I say Iceland is in Europe or North America?

In almost every school test or simple quiz, the expected answer is that Iceland is in Europe. Teachers and exam writers follow the usual political and cultural regions, not tectonic plates. You can add a note that Iceland lies on both the North American and Eurasian plates if you want to show extra knowledge.

Is Reykjavík on the North American plate or the Eurasian plate?

Reykjavík sits in southwest Iceland, close to where the plates meet, and most geologists place it on the North American plate side of the rift. However, the whole area is influenced by the spreading between plates, which is why the region has active volcanoes and frequent minor earthquakes.

Does Iceland count as part of Scandinavia or just the Nordic region?

Strictly speaking, “Scandinavia” usually means Norway, Sweden and Denmark. Iceland is not always included in that narrow definition. Instead, it is part of the broader “Nordic countries” group, which includes Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, plus territories like the Faroe Islands and Greenland.

Is Greenland treated the same way as Iceland when it comes to continents?

No. Greenland sits on the North American tectonic plate and is normally counted as part of North America in physical geography. Politically it is an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark. Iceland, by contrast, is an independent state that most maps and organizations group with Europe, even though its geology connects to both plates.

Could Iceland ever be reclassified as a North American country?

It is very unlikely. Geologists already recognize that parts of Iceland rest on the North American plate, but political and cultural ties point firmly toward Europe. There is no move in international organizations, sports or trade to treat Iceland as a North American country. Future debates are much more likely to focus on how closely Iceland should integrate with European Union structures instead.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Iceland is built on top of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, with its western part on the North American plate and its eastern part on the Eurasian plate.

- Continents, tectonic plates and world regions are different systems, and Iceland highlights those differences clearly.

- Politically and culturally, Iceland is a Nordic and European country, integrated into European trade, travel and security structures.

- Atlases, UN geoschemes, sports bodies and travel platforms almost always place Iceland in Europe.

- The question “Is Iceland in North America or Europe?” is a useful tool for thinking more critically about how humans draw boundaries on maps.