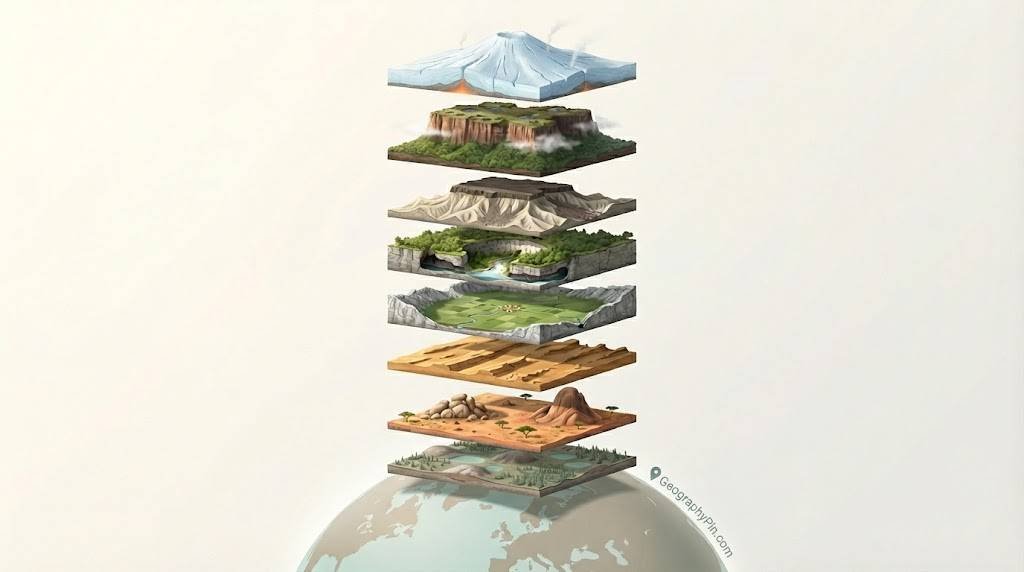

Rare landforms are uncommon natural features—such as nubbins, inselberg clusters, mega-yardangs, peneplains, tepuis, subglacial volcanoes, poljes, karst windows and inverted topography—that form under very specific conditions and occur in only a few regions worldwide. They record millions of years of erosion, climate change and volcanic activity.

What Do We Mean by “The World’s Rarest Landforms”?

When geographers call a landform “rare”, they do not mean that only one exists. Instead, they mean that the landform needs a very narrow set of conditions, appears in only a few regions, or is hard to recognise without expert tools such as satellite images. Mega-yardangs in the Lut Desert, subglacial volcanoes under Antarctica, or lava-filled inverted valleys in Utah all fit this idea. They are part of everyday Earth processes, but arranged in unusual ways. Many of these landforms are also relict, which means they formed under past climates or tectonic settings and have survived mostly as fossils in the modern landscape. A low, almost flat peneplain can be the worn-down surface of an ancient continent. A nubbin field of granite domes can be a leftover from warmer, wetter times, even if today’s climate is dry. For scientists, such “rare” shapes are time capsules: by measuring their height, age, and rock type, researchers can reconstruct how rivers, winds, ice and underground water shaped a region over tens of millions of years.

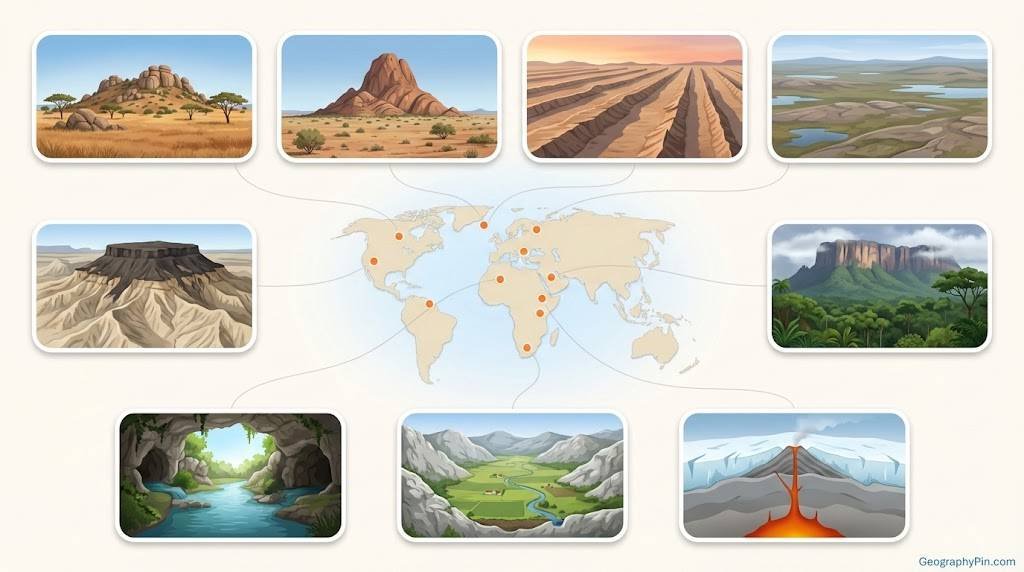

Overview: Nine Rare Landforms at a Glance

In this article we focus on nine rare landforms that are uncommon because they need very specific rock types, climate or tectonic history, and often survive as relict time capsules of past conditions.

| Landform | How It Forms | Typical Scale | Flagship Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nubbin | Granite hill with rounded boulders created by deep weathering and later exposure. | Tens of feet to a few hundred feet (10–100 m) high. | Granite nubbins in the MacDonnell Ranges, central Australia. |

| Inselberg cluster | Groups of hard-rock hills left standing as softer rock around them erodes away. | From small knobs a few dozen feet high to peaks several hundred feet (100+ m). | Mount Mulanje inselberg massif, Malawi, rising about 9,850 ft (3,002 m). |

| Mega-yardang | Wind-abraded ridges and grooves cut into soft rock in extremely dry deserts. | Ridges tens of feet high and hundreds to thousands of feet (tens to thousands of meters) long. | Kalut yardangs of the Lut Desert, Iran. |

| Peneplain | Almost-flat erosion surface made by long-term river action on stable continental crust. | Can cover tens of thousands of square miles (tens of thousands of square kilometers). | Laurentian peneplain of the Canadian Shield. |

| Tepui (outside Venezuela) | Flat-topped sandstone table mountain with steep cliffs, often isolated from surrounding forest. | Rise 3,300–9,800 ft (1,000–3,000 m) above nearby lowlands. | Mount Roraima at the border of Guyana, Brazil and Venezuela, summit about 9,219 ft (2,810 m). |

| Subglacial volcano | Volcano erupting beneath a glacier or ice sheet, creating pillow lavas and meltwater floods. | Individual edifices a few miles (several kilometers) wide; flood paths can extend tens of miles. | Grímsvötn volcano beneath the Vatnajökull ice cap, Iceland. |

| Polje | Large enclosed karst basin formed by merged sinkholes and solution of limestone. | Up to about 250 km² (around 100 sq mi); walls 165–330 ft (50–100 m) high. | Livanjsko polje and other basins of the Dinaric Alps, southeast Europe. |

| Karst window | Sinkhole where a cave roof has collapsed, revealing an underground river at the surface. | From a few dozen feet to hundreds of feet (10–100+ m) across. | Karst windows in Kentucky’s limestone country, USA. |

| Inverted topography | Former valleys filled with resistant rock (often lava) that now stand up as ridges. | Ridges and mesas rising hundreds of feet (tens to hundreds of meters) above today’s valleys. | Lava-capped mesas near St. George, Utah, USA. |

Granite Islands: Nubbins and Inselberg Clusters

What is a nubbin?

Nubbins look like small, friendly hills dotted with rounded boulders. In reality they are the exposed tips of deeply weathered granite. For long periods, water seeps into sheet fractures underground and breaks the outer shells of granite into blocks. When erosion strips away the softer material, a gentle hill remains, covered in weathered boulders that once sat below the surface.

You see this style in parts of the southwestern United States, in central Australia and in dry parts of southern Africa, often arranged in patterned groups. Because the weathering front moves slowly downward, different nubbins in the same area can record different stages of this deep-weathering process in three dimensions.

What is an inselberg cluster?

Inselberg clusters are the larger cousins in this granite story. An inselberg is an isolated hill or mountain rising abruptly from a plain; the word comes from German for “island mountain”. Where the resistant rock is widespread, you do not get just one “island” but an archipelago of them, sometimes mixed with smaller nubbins and tors.

In Malawi, the Mulanje Massif towers more than 9,800 ft (about 3,002 m) above the surrounding plains. In Mozambique, Mount Gorongosa rises over 6,100 ft (1,863 m). In Nigeria, Wase Rock stands nearly 980 ft (about 298 m) above the local surface. These peaks show how long erosion has been stripping away softer rocks around them while hard cores stand firm.

Why Granite Landforms Love “Old” Landscapes

Nubbins and inselberg clusters develop best on long-stable crust where tectonic activity is low. In such places, weathering can work quietly for tens of millions of years, slowly rounding corners and opening fractures. Geologists often find these granite hills sitting on old continental shields, like forgotten pieces of an earlier topography.

By dating minerals in the rocks and in the soils around them, researchers can estimate when deep weathering zones formed and link them to past climates that were warmer or wetter than today. In this way, a granite landscape becomes both a scenic destination and a history book written in boulders and domes.

Wind, Water and Time: Mega-yardangs, Peneplains and Tepuis Beyond Venezuela

What are mega-yardangs?

Mega-yardangs are wind-sculpted ridges and troughs carved into soft rock in deserts. They form where strong, very dry winds blow in one main direction for long periods, blasting sand and dust against the ground like natural sandpaper. In Iran’s Lut Desert and parts of Egypt and Namibia, high-resolution satellite images show mega-yardangs tens of feet high and hundreds to thousands of feet long.

From above they look like regular combs or fleets of parallel ships. Their alignment records ancient wind directions, useful for reconstructing past desert climates and for comparisons with similar features on Mars. Even small shifts in ridge orientation can hint at changes in prevailing winds over thousands of years.

What is a peneplain?

Peneplains sit at the opposite extreme: instead of sharp ridges, they are almost flat. A peneplain is a low-relief surface created by protracted erosion under long-lasting tectonic stability. Rivers wear down highs, fill lows, and gradually reduce the land towards a common base level, often close to sea level.

Classic examples include parts of the Canadian Shield, where ancient crystalline rocks form gently rolling surfaces, and broad erosion surfaces in Africa and Brazil. These plains can extend for tens of thousands of square miles (tens of thousands of square kilometers) and preserve evidence of very old landscapes that were later uplifted, tilted or partially buried.

Tepuis beyond Venezuela

Tepuis extend the story into the sky. While most people associate tepuis with southern Venezuela, these sandstone table mountains also rise in western Guyana, northern Brazil and eastern Colombia. Mount Roraima, sitting at the tripoint of Venezuela, Brazil and Guyana, reaches about 9,219 ft (2,810 m) and has a summit plateau of nearly 19 square miles (50 square kilometers).

Because many tepuis stand as steep-walled mesas cut off from surrounding forest, they host isolated ecosystems with endemic plants, insects and amphibians. For biologists, they are natural laboratories; for geomorphologists, they are resistant caps left behind as softer rocks eroded away from the Guiana Shield.

Fire Trapped Under Ice: Subglacial Volcanoes

Subglacial volcanoes, also called glaciovolcanoes, erupt beneath glaciers or ice sheets. When hot magma reaches the base of the ice, it melts a cavity and produces pillow lavas, breccias and volcanic glass that pile up instead of flowing far away. The surrounding ice chills the lava quickly, shaping unusual steep-sided volcanoes that look very different from typical cones.

Iceland and Antarctica host many active or geologically recent examples, while Canada preserves older ones in British Columbia and Yukon. These volcanoes are often invisible at the surface, so researchers rely on radar, seismic surveys and satellite data to detect them and to estimate how much heat they release into the ice above.

One dramatic case occurred in 1996, when a subglacial eruption at Iceland’s Grímsvötn volcano melted an estimated 3 cubic kilometers of ice under the Vatnajökull ice cap. The meltwater drained suddenly in a jökulhlaup, a glacial outburst flood, that destroyed roads and bridges downstream.

Events like this show how fire-and-ice systems can reshape valleys in just days. In Antarctica, radar and gravity data reveal chains of subglacial volcanoes buried under more than a mile (over 1.6 km) of ice. Their slow melting can influence ice flow and, over long timespans, may contribute to ice-sheet instability and sea-level change. For climate scientists, these hidden volcanoes are important background noise that must be understood when predicting how ice sheets will respond to global warming.

Karst Surprises and Upside-Down Landscapes: Poljes, Karst Windows and Inverted Topography

What is a polje?

Karst landscapes form where soluble rocks like limestone and dolomite are dissolved by slightly acidic water. Over time this process produces sinkholes, underground drainage systems, caves and large enclosed basins. Among the largest of these features is a polje, an elongated basin with a flat floor and steep walls, often formed by the merging of many sinkholes.

Floors can reach about 250 square kilometers (around 100 square miles), while enclosing walls rise roughly 165–330 ft (50–100 m). Some poljes flood seasonally as rivers sink into swallow holes and reappear at springs along the edges. Farmers in the Dinaric Alps have used these fertile floors for centuries, even as they manage the flood risk with drainage channels and careful crop choices.

What is a karst window?

A karst window (karst fenster) is smaller but just as intriguing. Here, part of a cave roof collapses, revealing a section of an underground river at the surface. Water may emerge from one cave opening, flow briefly in daylight and then disappear back underground into another sinkhole nearby.

These windows provide rare, direct access to subterranean streams, which helps hydrologists trace pollution pathways and measure how quickly groundwater moves through limestone aquifers. They also act as natural skylights for cave ecosystems, letting in light and organic material that support specialised plants and animals.

How inverted topography works

Inverted topography flips our normal expectations. Imagine a river valley that becomes filled with resistant lava or welded ash. At first, the valley is still low, even though tougher rock now lines its floor. Over millions of years, the softer rocks on the valley sides erode away faster than the hard lava in the middle.

Eventually the former valley floor stands up as a ridge or mesa, while the old hills have become lowlands. This inside-out pattern is common in parts of the Colorado Plateau, especially near St. George in southern Utah, where lava-capped mesas mark the course of ancient rivers. Similar inverted ridges also appear in satellite images of Mars, where cemented river deposits now stand above the plains around them.

FAQ

Are these rare landforms still forming today?

Yes. Mega-yardangs continue to grow in very dry deserts where strong winds blow, subglacial volcanoes in Iceland and Antarctica can still erupt, and new karst windows open as cave roofs collapse. At the same time, many nubbins, peneplains and inselberg clusters are relict, meaning they mainly record past climates and erosion cycles.

Why don’t we hear about nubbins and poljes in school geography?

School textbooks usually focus on broad landform types that appear almost everywhere: mountains, rivers, coasts, glaciers. Nubbins, poljes or subglacial volcanoes need special rock types, climates or ice conditions, so they are less common and more technical. They tend to appear in university geomorphology courses or specialist field guides rather than basic school books.

Can you visit any of these rare landforms safely?

Some are accessible to hikers and tourists, such as certain inselbergs in Malawi and Mozambique, selected tepuis via guided expeditions, and karst landscapes in countries like Slovenia, Croatia or the United States. Others, like Antarctic subglacial volcanoes or fragile karst windows on private land, are off limits or require strict scientific permits to protect both visitors and the environment.

What do these landforms tell us about past climate and tectonics?

Each type records a different story. Peneplains and inselberg fields indicate long periods of tectonic stability and slow erosion. Mega-yardangs point to persistent strong winds in arid climates. Poljes and karst windows reflect long-term limestone solution and groundwater flow. Inverted topography captures the position of ancient valleys that may now lie hundreds of feet above nearby plains. Combined, they help reconstruct Earth’s history as of 2025 and beyond.

Do similar rare landforms exist on other planets?

Yes, at least in part. Yardang-like ridges appear on Mars and possibly on Venus, and inverted river valleys on Mars resemble lava-capped mesas in Utah. Scientists use Earth examples such as mega-yardangs in Iran or inverted topography in the Colorado Plateau as analogues to interpret planetary images and to understand wind, water and volcanic processes on other worlds.

What Did We Learn Today?

- “Rare” landforms often need very specific rock types, climates or ice conditions and may record ancient surfaces rather than modern ones.

- Nubbins and inselberg clusters grow from long-term granite weathering and stand as rocky islands above old plains.

- Mega-yardangs, peneplains and tepuis preserve wind, water and uplift histories across deserts and table mountains in South America and beyond.

- Subglacial volcanoes, poljes, karst windows and inverted topography show how hidden processes can reshape both underground and surface landscapes.

- Studying these features, with data checked as of 2025, helps scientists piece together Earth’s climate, tectonic and erosion history—and even decode landforms on other planets.