Taiga Biome (Boreal Forest): Location, Climate, Plants & Animals

The taiga, or boreal forest, is Earth’s largest land biome, a belt of mainly coniferous forest stretching across northern North America, Europe and Asia between about 50° and 70° north. It has long, cold winters, short cool summers, low to moderate precipitation, needle-leaf trees like spruce and pine, and cold-adapted animals such as moose, wolves and lynx.

Where Is the Taiga Biome Located?

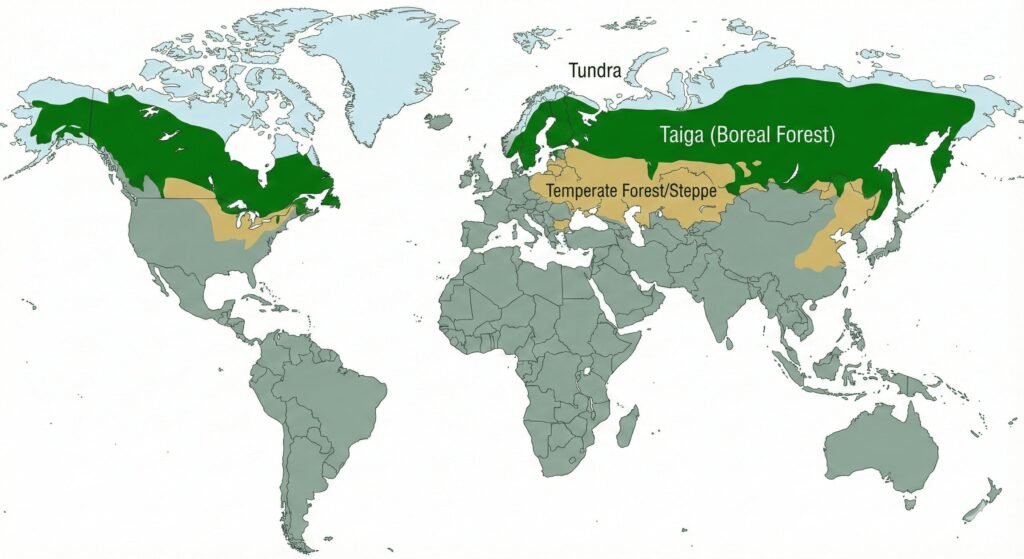

The taiga forms a nearly continuous belt of forest in the Northern Hemisphere, sitting between the treeless Arctic tundra to the north and temperate broadleaf or mixed forests to the south. In simple terms, if you move north from New York or Berlin toward the Arctic Circle, you eventually pass through this cool, dense conifer forest zone.

Most taiga lies between roughly 50° and 70° north latitude. It dominates inland Canada and Alaska, much of Scandinavia and Finland, and huge stretches of Russia and Siberia, with smaller patches in northern Mongolia, northern Kazakhstan, and northern Japan (Hokkaido).

By area, the taiga is the largest land biome on the planet. Estimates cluster around 17 million square kilometers (6.6 million square miles), equal to about 11–17 percent of Earth’s land surface and around one-third of global forest area. The biggest national shares are in Russia and Canada, each holding millions of square kilometers of boreal forest.

This forest belt is not just trees. In Canada alone, the boreal region contains about 25 percent of the world’s wetlands and more than 1.5 million lakes larger than roughly 10 acres (about 40,000 square meters), making the taiga one of the most lake-rich regions on Earth. These lakes, bogs and rivers are crucial for migratory birds and for storing water and carbon.

Taiga by the Numbers (as of 2025)

To get a quick “snapshot” of the taiga, it helps to look at a few key metrics. The table below summarises size, climate and ecological importance using values from recent boreal-forest syntheses and climate descriptions.

| Metric / Year | Value / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Global taiga area | ≈17 million km² (6.6 million mi²) of largely continuous boreal forest. |

| Share of Earth’s land | Roughly 11–17% of all land area, depending on where boundaries are drawn. |

| Typical latitude band | Mostly between 50°N and 70°N, between Arctic tundra and temperate forests. |

| Mean annual temperature | Around −5 to +5 °C (23–41 °F); some eastern Siberian taiga sites are colder. |

| Annual precipitation | About 200–750 mm (8–30 in), sometimes up to ~1,000 mm (39 in), mostly summer rain plus winter snow. |

| Typical growing season | Roughly 50–130 days (about 2–4 months) with mean daily temperatures above 5 °C (41 °F). |

| Share of forest carbon sink | Boreal forests hold about 29% of global forest area and around 20% of the forest carbon sink, plus a large share of global soil carbon. |

Taiga Climate, Seasons & Growing Season

The taiga has a classic subarctic climate: long, cold winters and short, cool to mild summers. In many taiga locations, the average temperature in the coldest month is below −10 °C (14 °F), and in far eastern Siberia mean winter temperatures can drop to around −50 °C (−58 °F). These harsh conditions shape every plant and animal that lives here.

Over the whole year, mean annual temperatures usually sit between about −5 and +5 °C (23–41 °F), placing the taiga just warmer than tundra but colder than temperate forests. In winter, high-pressure systems can trap cold air over the continents so that inland areas of Russia, Canada and Alaska experience very low temperatures for months, with snow covering the ground for much of the year.

Summers are brief but surprisingly bright. Typical summer temperatures range from about 10 to 20 °C (50–68 °F), and daytime highs can occasionally reach around 25 °C (77 °F). However, the growing season is short: in many boreal regions only 50–100 days are frost-free, and even in milder coastal taiga it is rarely longer than 145–180 days.

Precipitation is low to moderate compared with tropical or temperate forests. Most taiga receives about 200–750 millimeters (8–30 inches) of water each year, with some wetter areas in northern Europe and eastern North America reaching roughly 1,000 millimeters (39 inches). Much of this falls as summer rain, while winters bring snow and sometimes fog. Because evaporation is limited by low temperatures, this amount of moisture is enough to support dense forest and extensive wetlands.

Snow can stay on the ground for 6–9 months in the northern taiga, insulating soils and influencing whether permafrost forms. In some Siberian and Canadian subregions, frozen ground (permafrost) lies close to the surface, restricting root depth and drainage. Farther south, deeper, seasonally thawed soils allow taller, denser forests. This gradient from frozen, waterlogged soils to better-drained ones helps explain why tree height and species mix change from the tundra edge down toward more temperate climates. In many regions, the dominant soil type is a thin, acidic, nutrient-poor soil known as podzol, formed as organic acids from conifer needles leach minerals downward and leave a pale, ash-like layer beneath the surface.

Another key feature is light. In mid-summer the high-latitude taiga experiences very long days, sometimes with twilight instead of full night. Plants use this “light bonus” to photosynthesise intensely during their short growing period, and many animals time reproduction around this brief window of warmth and food.

Plants, Animals and Adaptations in the Taiga

The taiga is dominated by a small group of hardy conifer trees: pines (Pinus), spruces (Picea), firs (Abies) and larches (Larix). These species can survive freezing winters, poor soils and short summers better than most broadleaf trees. In many regions, they form dense, dark green stands that give the boreal forest its characteristic look from satellite photos.

Needle leaves are a key adaptation. Evergreen needles are narrow, covered in a waxy coating and stay on the tree for several years. This reduces water loss, protects against frost damage and allows trees to start photosynthesis quickly each spring, without waiting to grow new leaves. The conical shape of many spruces and firs also helps snow slide off branches, reducing breakage during heavy snowfalls.

Although conifers dominate, taiga forests are not pure “Christmas tree farms.” Deciduous trees such as birch (Betula), aspen and poplar grow especially along rivers, lakes and in disturbed areas after fire or logging. The forest floor often has thick moss carpets, lichens, heath shrubs (like blueberries and Labrador tea) and peat-forming plants in wetter spots. Because the climate is cold and soils are often waterlogged and acidic, decomposition is slow and organic matter can build up, creating peat and carbon-rich layers.

The taiga’s animals are adapted to a world of snow, short summers and long distances. Large herbivores such as moose, elk and caribou (reindeer) browse on twigs, shrubs, aquatic plants and ground vegetation. Moose are among the largest animals here, with long legs suited to deep snow and wetlands. Woodland caribou often use quiet, old-growth taiga where they can feed on ground and tree lichens during winter.

Predators include gray wolves, Eurasian and Canada lynx, wolverines and bears (brown, black and, near the Arctic coast, polar bears). Smaller mammals such as snowshoe hares, red squirrels, voles, lemmings and martens form the “middle” of the food web and are important prey for both mammals and birds. Many species grow thick winter coats, change fur colour to white for camouflage in snow, or use hibernation and torpor to save energy.

The taiga also supports huge numbers of birds. Owls and hawks hunt rodents; woodpeckers feed on insects living under bark; crossbills and other finches specialise in extracting seeds from cones. Each spring and summer, millions of migratory songbirds and waterbirds arrive from temperate and tropical regions to raise their young in taiga wetlands and forests, taking advantage of the insect boom during the light-filled growing season.

Beyond its wildlife, the taiga is a global climate regulator. Boreal forests store enormous volumes of carbon in trees, dead wood, peat and frozen soils—potentially more per square mile (square kilometer) than tropical forests in some regions. When fires, logging or thawing permafrost release this carbon, it enters the atmosphere as greenhouse gases. In recent years, global datasets have shown record forest loss driven largely by fires, with boreal regions in Canada and Siberia contributing significantly to burned area. Satellite studies also confirm that the boreal tree line has shifted northward over the last few decades, reflecting warming temperatures and changing snow patterns.

FAQ

Where is the taiga biome found in the world?

The taiga biome forms a broad band across the Northern Hemisphere. It covers much of inland Canada and Alaska, most of Scandinavia and Finland, and huge areas of Russia and Siberia, with smaller patches in northern Mongolia, northern Kazakhstan and northern Japan (Hokkaido). It lies between tundra to the north and temperate forests to the south.

How cold does the taiga get in winter?

Winters in the taiga are very cold. Average January temperatures are often below −10 °C (14 °F), and inland parts of eastern Siberia can reach mean winter temperatures near −50 °C (−58 °F). Individual record lows have been close to −60 to −67 °C (−76 to −89 °F) in some Siberian valleys.

What kinds of plants grow in the taiga?

The main trees are cold-tolerant conifers such as spruce, pine, fir and larch. In many areas you also find birch, aspen and poplar, especially along rivers or after fires. The forest floor often has thick mosses, lichens, low shrubs like blueberries and Labrador tea, and peat-forming plants in bogs and fens.

What animals live in the taiga biome?

Large herbivores include moose, elk and caribou (reindeer). Predators include gray wolves, lynx, wolverines and several bear species. Smaller mammals such as snowshoe hares, red squirrels, voles and lemmings are common, and many owls, hawks, woodpeckers, crossbills and migratory songbirds use the taiga for feeding and breeding.

Why is the taiga important for Earth’s climate?

The taiga stores tremendous amounts of carbon in trees, peat and frozen soils, acting as a long-term carbon sink. Boreal forests make up close to a third of global forest area and contribute roughly one-fifth of the forest carbon sink, while also influencing how much sunlight the planet reflects back into space. Disturbances like fires and permafrost thaw can release this stored carbon.

How is climate change affecting the taiga biome?

Warming temperatures are lengthening growing seasons in some regions and causing the boreal tree line to move northward, while also increasing drought stress and fire risk. Recent datasets show record forest loss linked to fires, and studies confirm northward migration of boreal tree cover between the 1980s and 2020s. Permafrost thaw and more frequent extreme fire seasons could turn parts of the taiga from a carbon sink into a carbon source.

What Did We Learn Today?

- The taiga is Earth’s largest land biome, covering about 17 million km² (6.6 million mi²) across North America, Europe and Asia.

- It sits between tundra and temperate forests in the Northern Hemisphere, mostly from 50°N to 70°N.

- The climate features long, cold winters, short cool summers, 200–750 mm (8–30 in) of annual precipitation and short growing seasons of about 50–130 days.

- Conifer trees like spruce, pine, fir and larch dominate, with hardy shrubs, mosses, lichens, peatlands and thin, acidic podzol soils below them.

- The taiga supports moose, caribou, wolves, lynx, bears and countless birds, while storing vast amounts of carbon that strongly influence global climate.