Many capital cities now operate aerial gondolas as part of their public transit networks rather than solely for tourism. These urban cable car systems use suspended cabins to carry commuters over difficult terrain and congested streets. For example, La Paz in Bolivia, Mexico City, and Bogotá built cable cars that transport tens of thousands of passengers daily, cutting commute times by up to 50% and connecting isolated hillside neighborhoods with city centers. Unlike tourist cable cars, these systems integrate with local transit, helping reduce traffic and pollution while providing fast, reliable rides.

Why Capital Cities Are Embracing Urban Cable Cars

In many cities—especially those on rugged terrain or facing extreme traffic—cable cars offer a creative urban mobility solution. These systems, also known as aerial tramways, gondola lifts, or teleféricos, glide above congested streets and climb grades that buses and cars struggle with. By stringing cables between towers, a city can connect hard-to-reach districts without expensive tunneling or road-building. The physical footprint is minimal—small tower bases and stations—so dense neighborhoods avoid demolition. For rapidly growing capitals, cable cars are a cost-effective, quick-to-build option compared to new subway lines or highways. They also run on electricity, giving them a low carbon footprint and helping cut air pollution by replacing diesel vehicles.

Inclusion, Integration, and Purpose

Another driving factor is social inclusion. Many lower-income communities occupy steep hills at a city’s edge, where road access is limited. Urban gondolas bridge these “topographical barriers,” connecting isolated neighborhoods to jobs and services. Medellín (2004) pioneered the model. Soon after, capital cities like Caracas and La Paz followed, linking marginalized barrios with main transit lines. By literally elevating public transit, cities reduce congestion and improve mobility for those who need it most. As one La Paz project leader observed, in a built-up city the practical options are “huge road projects—or install urban cable cars.” Crucially, these systems are designed for daily commuters, not sightseers. They integrate with bus or metro networks and are priced affordably. Below, we explore capital cities that successfully implemented cable cars as public transit, showing how each addresses unique urban challenges.

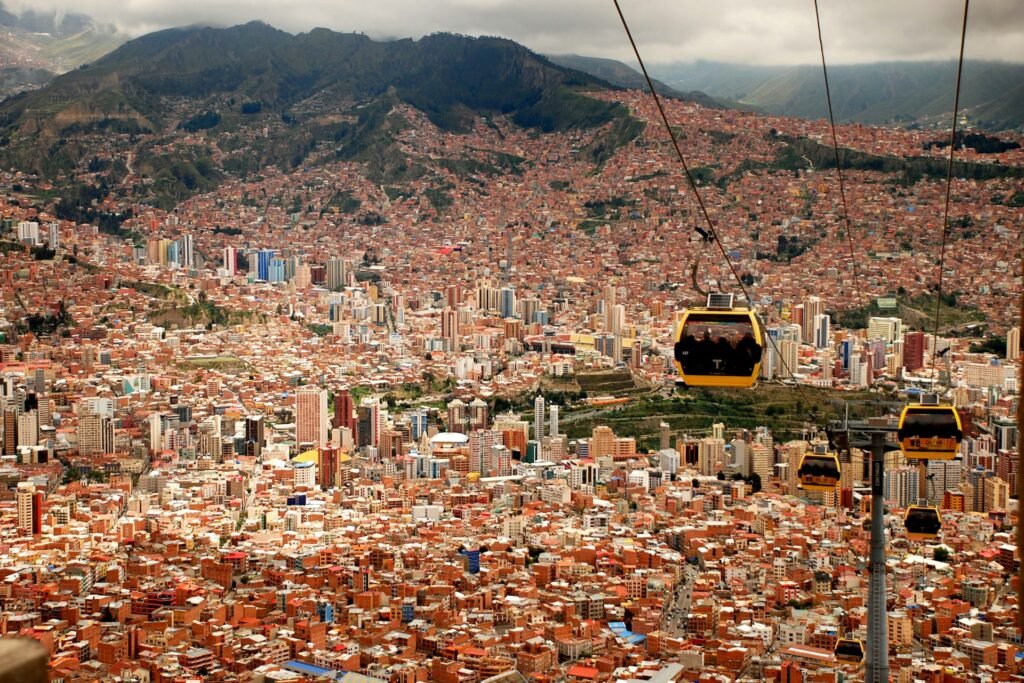

La Paz, Bolivia – Mi Teleférico: Backbone of Transit

Gondola cabins of Mi Teleférico soar above La Paz. This extensive cable car network carries hundreds of thousands of commuters between the Bolivian capital and neighboring El Alto each day. La Paz’s Mi Teleférico (“My Cable Car”) is the world’s largest urban cable car network and a showcase for cable transit. Opened in 2014, it connects the high-altitude city of El Alto with central La Paz, which lies 400 m (1,300 ft) below in a canyon. Before, commuters spent over an hour zigzagging on jam-packed roads. Today, they can hop on at the cliff’s edge in El Alto and descend to La Paz in minutes, often cutting travel time nearly in half. At rush hour, the contrast is stark—a serene 10-minute gondola ride versus a slow crawl in minivans or buses.

Network, Cost, and Operations

Mi Teleférico began with three color-coded lines (Red, Yellow, Green) spanning about 10 km. At launch, the system could move up to 18,000 passengers per hour over nearly 11 km. Gondolas depart every 12 seconds and seat 8–10 people. Phase 1 cost about $234 million, funded by Bolivia’s government and built by Austrian firm Doppelmayr. Fares were set low (about 3 bolivianos, ~$0.45) to compete with minibuses and keep trips affordable.

Impact and Growth

Across multiple expansions, Mi Teleférico grew to 10 lines with 36 stations by 2019. It functions as the transit backbone for La Paz–El Alto. By 2017, ridership averaged about 243,000 passengers per day, with capacity for more as lines expanded. Travel times fell, reliability improved, and road disruptions or landslides mattered less. The system also reduced fuel use and pollution by replacing vehicle trips and earned a 2018 Latin American “Smart City” award for sustainable mobility. Today, La Paz’s colorful cabins crisscross the skyline, symbolizing a shift from street congestion to sky-based mass transit.

Mexico City, Mexico – Cablebús: Cutting Commutes Over Gridlock

Mexico City, one of the world’s largest capitals, opened Cablebús in 2021 to tackle traffic and inequality. Sprawling districts in the hills of Iztapalapa and Gustavo A. Madero faced long, difficult commutes. Cablebús Lines 1 and 2 connect these neighborhoods to the metro and Bus Rapid Transit corridors. Trips that once took over an hour by multiple buses now take about 30 minutes by cable car, reducing commute times by up to 45%. Each line spans roughly 9–10 km, with intermediate stations serving dense areas that lacked efficient transit.

Who It Serves and What Changed

The modern gondolas have high capacity. Together, Lines 1 and 2 serve over 100,000 riders daily, showing pent-up demand for better transit. Line 1 (Cuautepec to Indios Verdes) dramatically increased residents’ access to jobs, schools, and services within a one-hour travel radius. Surveys found improved access to employment, education, and leisure once the cable cars arrived.

Environmental and Social Gains

Because Cablebús runs on electricity, the city estimated it cut about 18,500 tons of CO2 in its first two years by displacing car and bus trips. Stations came with upgrades to nearby public spaces—new walkways, lighting, and markets—uplifting the neighborhoods they serve. Fares remain low (around 7 pesos, ~$0.35) and integrate with the broader fare card. As the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy notes, urban gondolas succeed when they integrate with existing networks and meet real demand. Mexico City’s Cablebús now forms an essential part of the capital’s transit mix, lifting commuters out of gridlock—literally.

Bogotá, Colombia – TransMiCable: Connecting Communities

The bright hillside of Ciudad Bolívar in Bogotá is served by the red cabins of TransMiCable. This line halved travel times for 20,000+ daily riders in this low-income district. Colombia’s capital inaugurated TransMiCable in late 2018, targeting one of the city’s poorest and most isolated areas: Ciudad Bolívar. Perched on steep hills in the far south, this district of 700,000 once endured 2-hour commutes on multiple buses to reach jobs across town. The cable car changed that almost overnight. The 3.5 km line with 4 stations now carries about 20,000 people a day in gondolas with solar panels on the roof. A ride that used to take 40–50 minutes by road is now a swift 13–15 minutes by cable. For the price of a bus fare (around 2,700 pesos, <$1), locals get a safe, quick trip above once-treacherous footpaths.

Integration and Public Space

TransMiCable extends Bogotá’s BRT system, TransMilenio. Its terminus connects to the Tunal bus portal, so residents of the high barrios can transfer to the city’s main arteries easily. The project paired mobility with social goals: new libraries, community centers, and playgrounds appeared around stations. Homes along the route were painted in vibrant colors, building local pride. Reported crime declined as stations added lighting, activity, and “eyes on the street.”

Environment and Daily Life

The largely solar-powered system reduces emissions by displacing diesel trips on the hills. For residents like a nanny quoted by Reuters, TransMiCable simply saves time and lowers stress. She now gets home in 30 minutes, not 90, and has more time with family. Bogotá shows that even without a metro, a cable car can connect a marginalized hillside to opportunity while symbolizing renewal.

Caracas, Venezuela – Metrocable: Social Inclusion in Transit

Caracas, shaped by a dramatic valley, launched Metrocable in 2010 to bring transit to hillside barrios long cut off from the urban core. The first line rose in San Agustín, a dense neighborhood on a 200 m slope above downtown. Before, residents navigated stairs and unreliable jeep-taxis to reach the nearest metro station. Metrocable changed daily life: one resident said they once woke at 5:00 a.m. to reach work by 8:00; now they leave later and avoid exhausting climbs. The line spans 1.8 km with 5 stations and carries about 15,000 people per day as part of the metro network. A trip that once took an hour now takes about 9 minutes by gondola.

Community Hubs and Dignity

Stations were designed as community hubs. Plans included daycare centers, markets, and training spaces, and residents were trained and hired to operate the system. That created jobs and a sense of ownership; local leaders noted that the community protects the cabins from vandalism. Despite economic challenges, a second line later opened in Mariche. Reliability has varied, but the system remains a lifeline and a visible symbol of inclusion.

Ankara, Turkey – Şentepe Teleferik: An Alternative to Traffic

Not only Latin American capitals turn to cable cars. In Ankara, Turkey’s capital, a gondola line addressed traffic and topography in the Şentepe district. The Yenimahalle–Şentepe Teleferik opened in 2014, creating an aerial link from a metro station to a hilltop residential area. The cable car covers about 3.3 km with 4 stations, climbing roughly 200 m in elevation. Unusually, it launched as part of the public network and is free to ride for passengers who present a transit card.

Operations and Reception

Each cabin holds 10 people, and the line can move up to 2,400 passengers per hour per direction. Cabins arrive about every 15 seconds, and the end-to-end ride takes 13–15 minutes. The cable car works in sync with the metro and helps relieve traffic by intercepting commuters who might otherwise drive up the hill. It is accessible—strollers and wheelchairs can roll on—and runs even in snowy winters. Ankara’s success is now watched by other Turkish cities.

| Capital City | Cable Car System | Year Opened | Length / Stations | Daily Ridership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Paz (Bolivia) | Mi Teleférico | 2014 (Phase 1) | 30.6 km, 10 lines, 36 stations | ~243,000 (2017 avg) |

| Mexico City (Mexico) | Cablebús (Lines 1 & 2) | 2021 | Line 1: 9.2 km; Line 2: 10.6 km (6 stations each) | 100,000+ (two lines) |

| Bogotá (Colombia) | TransMiCable | 2018 | 3.34 km, 4 stations | ~20,000 |

| Caracas (Venezuela) | Metrocable (San Agustín line) | 2010 | 1.8 km, 5 stations | ~15,000 |

| Ankara (Turkey) | Yenimahalle–Şentepe Teleferik | 2014 | 3.26 km, 4 stations | 2,400 pphpd capacity (free fare) |

Public Transit vs Tourist Gondolas: Not All Cable Cars Are Equal

It’s important to note that not every capital’s cable car succeeds as transit—some rides remain tourist-oriented.

Quito’s TelefériQo

Quito’s TelefériQo (note the “Q” for Quito) opened in 2005 and carries visitors from the city (~3,000 m altitude) up Pichincha Volcano to a lookout over 4,000 m high. The 2.5 km journey offers breathtaking views but doesn’t function as daily public transport. The upper station is a viewpoint and trailhead, not a residential or job center. Locals use it mainly for recreation, and pricing reflects that—much higher than a bus fare.

London’s Cross-River Cable Car

London attempted to blend tourist appeal with commuting via the Emirates Air Line (now the IFS Cloud Cable Car). Opened ahead of the 2012 Olympics, it spans the River Thames in east London and is part of Transport for London. However, its location and fares made it impractical for most residents. Within a year, only a handful of regular commuters used it consistently, and ridership fell year-over-year. Because it wasn’t fully integrated with common fare products and sits away from typical travel patterns, it became known as a “white elephant.” Today, it mostly serves visitors seeking views of the O2 Arena and Thames Barrier. The lesson: successful urban gondolas sit where people need to go and integrate seamlessly with the broader network and fares.

Future Outlook: More Capital Cable Car Projects

Early successes in Latin America spurred many capitals to consider cable cars for transit. A new wave of projects is on the horizon.

Europe

Paris, France plans to open its first urban cable car (the Câble C1) by 2025. The 4.5 km gondola will link Créteil and Villeneuve-Saint-Georges in the southeast of the metro area and aims to carry ~11,000 passengers per day. While not in the dense center, it shows major European capitals view gondolas as tools for tough suburban commutes.

Africa

In Kigali, Rwanda, plans are underway for what could be Africa’s first modern urban cable car network, targeting a 5.5 km line by 2028. The project would move 50,000+ passengers daily in about 15 minutes end-to-end and integrate fully with the city’s transport grid. Nairobi and Kampala have explored related ideas to tackle congestion.

Americas and Beyond

Latin American capitals continue to expand. Bogotá is planning additional TransMiCable lines to other hilly sectors. Mexico City is considering more Cablebús routes and further metro-area gondolas. La Paz–El Alto keeps extending Mi Teleférico. In North America, Washington, D.C., has floated a Potomac gondola linking Georgetown.

Big Picture

Momentum suggests cable transit is shifting from novelty to mainstream option. Technology advances and proof-of-concept successes point to more capital cities joining the trend. Cable cars aren’t a cure-all, but they excel where geography and congestion meet limited mobility. In those settings, they can become “a scalable model of low-carbon, inclusive public transport,” as advocates note. From Asia to Africa to Europe, more commuters may soon ride the sky to work.

FAQ

Which capital cities use cable cars for commuting?

Several national capitals now run cable cars as part of their transit systems. Notable examples include La Paz (Bolivia) with the extensive Mi Teleférico network, Mexico City (Mexico) with Cablebús, Bogotá (Colombia) with TransMiCable, Caracas (Venezuela) with Metrocable, and Ankara (Turkey) with the Şentepe teleferik. These systems carry daily commuters and integrate with each city’s broader network. Other capitals like Quito (Ecuador) and London (UK) have cable cars as well, but those function mainly as tourist attractions rather than commuter lines.

How do urban cable cars reduce traffic congestion?

Cable cars let commuters fly over traffic. By moving people in the air, they remove riders from clogged roads. In La Paz and El Alto, cable cars replaced thousands of minibus trips, easing congestion. In Mexico City, Cablebús helps residents of far-flung neighborhoods reach metro stations without driving, which reduces cars on the road. Each line can carry 3,000–6,000 passengers per hour per direction, rivaling several bus lines without adding street traffic. Reliable travel times also attract people who might otherwise drive.

Are urban gondolas a serious form of public transport or just a gimmick?

When planned well, urban gondolas are a serious form of public transport. Evidence comes from ridership and integration. La Paz carries over a quarter million riders a day, forming a backbone of city transit. Mexico City serves over 100,000 daily riders and improves commute times and local economies. These systems are engineered for reliability and safety. Gondolas work best in specific scenarios—hilly cities or river crossings—and are not a one-size-fits-all solution. Where placement and fares miss real needs, as in parts of London, they feel gimmicky. In the right context, they are efficient, cost-effective options.

What are the benefits of aerial tramways in cities versus buses or trains?

1. Climbing hills with ease: Gondolas handle very steep grades without costly tunneling or switchback roads. 2. Avoiding traffic: They run above ground, so congestion doesn’t slow them. Travel time stays consistent and often faster than by road. 3. Lower infrastructure footprint: Cable cars need only towers and compact stations, minimizing land acquisition or demolition in dense areas. 4. Cheaper and quicker to build: Compared to a subway or highway, cable car lines cost less and can be built within 1–2 years, then extended modularly. 5. Environmentally friendly: Electric power means no direct emissions and fewer diesel buses, cutting air pollution and CO2. 6. Safe and accessible: Gondolas have strong safety records and are accessible to older adults and people with disabilities; platforms are level and cabins can slow for boarding.

How much does it cost to build and ride an urban cable car system?

Costs vary with length and station count. For example, La Paz’s first three lines (11 km) cost about $235 million—roughly $21 million per km—cheaper than an underground metro. Mexico City’s 10 km Cablebús Line 2 was about $158 million (around $15.8 million/km). Factors include terrain, fleet size, and imported technology. Operating costs are relatively low once built because cabins are automated and electric. Fares are usually affordable, similar to a bus fare, and often integrated on one transit card. In many Latin American systems, a one-way ride costs under $1. Ankara’s cable car is free with a metro pass. Tourist-centric systems (e.g., Quito, London) charge more, but commuter-focused gondolas aim to stay accessible.

Do cable cars work in bad weather and at night?

Modern systems operate in varied conditions. They run in rain and moderate wind. In La Paz and Caracas, heavy rains cause only occasional interruptions. High winds are the main concern—above about 50–70 km/h (30–45 mph), operations may pause for safety. Urban routes are often more sheltered than alpine lifts, so extreme winds are rarer. At night, stations and cabins are lit, and many systems run into late evening—some for about 17 hours a day. Most close around midnight for overnight maintenance. In short, they are all-weather capable with brief pauses during severe storms or lightning.

Which upcoming cities will launch cable car transit next?

Paris, France is on track to open the Câble C1 gondola by 2025 in its metro area—the first in that region. Kigali, Rwanda aims to launch Africa’s first urban cable car by 2028, with a 5.5 km line planned. In Latin America, Santiago, Chile (not a capital) has a transit gondola in development, and Buenos Aires, Argentina has discussed one. In Asia, Manila (Philippines) and Kathmandu (Nepal) have studied proposals. Second-generation projects are also emerging: Medellín continues to expand; Rio de Janeiro may revive and extend earlier favelas lines. As congestion and pollution push cities toward creative solutions, expect more announcements within the decade.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Several capital cities—including La Paz, Bogotá, and Mexico City—successfully implemented urban cable car systems as public transit, moving tens of thousands of commuters daily.

- Urban gondolas can dramatically cut commute times in hilly or congested cities. For example, Mexico City’s Cablebús reduced travel times by up to 45% for hillside riders.

- These systems often serve social inclusion goals, connecting isolated low-income communities to city centers and opportunities (e.g., Bogotá’s TransMiCable halved a 2-hour commute to about 16 minutes).

- Cable cars are eco-friendly, low-footprint transit. They run on electricity, help reduce pollution, and require far less land and infrastructure than highways or rail lines.

- Success hinges on integration: cable cars used as true public transit with strategic routes and integrated fares thrive, while tourist-focused lines see lower local use.