Lake Baikal: World’s Deepest Lake – Depth, Location & Wildlife

Lake Baikal is a huge rift lake in southern Siberia, Russia. It has a maximum depth of about 5,387 feet (1,642 meters) and holds roughly 20–23% of the world’s unfrozen surface freshwater. It is the deepest and largest freshwater lake by volume on Earth, famous for its clear water and thousands of endemic species.

Where Is Lake Baikal? Map, Coordinates & Regional Setting

Lake Baikal lies in south-eastern Siberia, in the Asian part of Russia. It sits between two federal regions: Irkutsk Oblast on the northwest shore and the Republic of Buryatia on the southeast shore. On a globe, Baikal is roughly halfway between Moscow and Beijing, with its central part near 53°N, 108°E.

The lake occupies a long, crescent-shaped basin trending from southwest to northeast. Its surface area is about 12,200 square miles (around 31,500–31,722 square kilometers), which makes it slightly larger than Belgium. Baikal is Asia’s largest freshwater lake by surface area and the world’s seventh-largest by area, but its real superpower is depth and volume.

Baikal’s watershed extends into both Russia and Mongolia, with hundreds of rivers and streams feeding the lake. The Selenga River from Mongolia is the biggest inflow, while the Angara River at the northwestern end is the only outflow. This simple “one outlet” system helps scientists track changes in water balance, climate and pollution more easily than in lakes with many exits.

Lake Baikal by the Numbers

The table below brings together the headline facts students and teachers usually need for projects, infographics and quick comparisons.

| Metric | Value (Imperial & Metric) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum depth | ≈5,315–5,387 ft (1,620–1,642 m) | Sources differ slightly; all agree Baikal is the deepest freshwater lake. |

| Average depth | ≈2,440 ft (≈744 m) | Very deep compared with most large lakes. |

| Length | 395 mi (636 km) | From southwest to northeast. |

| Maximum width | 49 mi (79 km) | Widest in the central basin. |

| Surface area | ≈12,200 sq mi (≈31,500–31,722 km²) | Slight variations reflect different mapping methods. |

| Water volume | ≈5,500–5,670 cu mi (≈23,000–23,600 km³) | About one-fifth of the world’s unfrozen surface freshwater. |

| Age | ≈25–30 million years | One of the oldest lakes in geological history. |

| UNESCO World Heritage | Inscribed 1996 | Listed for age, depth, biodiversity and scenery. |

How Deep and How Big Is Lake Baikal?

Depth, Volume and Water Clarity

Baikal is not only deep; it is also huge in terms of stored water. Its maximum depth of around 5,315–5,387 feet (1,620–1,642 meters) makes it the world’s deepest freshwater lake. The average depth of about 2,440 feet (744 meters) means that even “ordinary” parts of the lake would count as deep in most other countries.

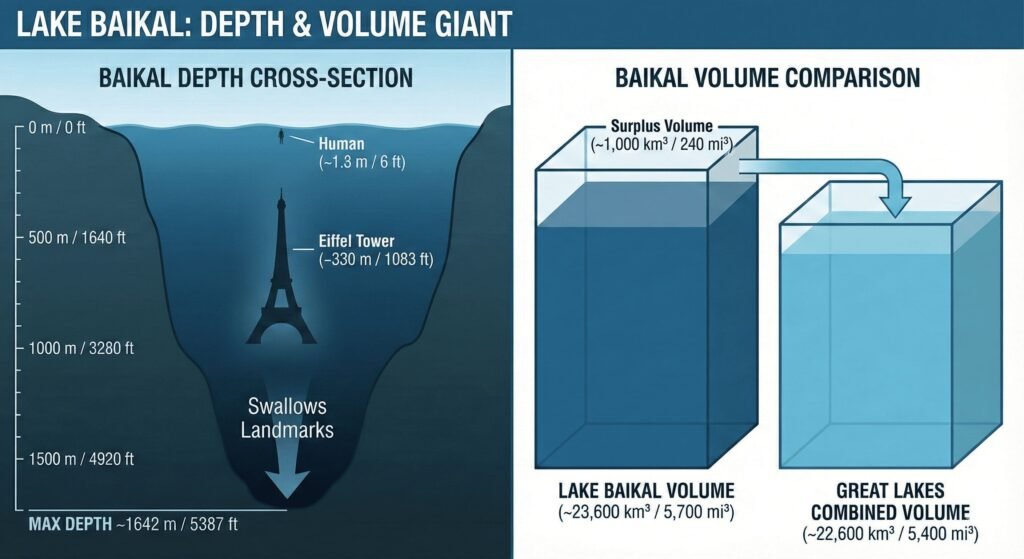

Because the lake is both deep and wide, its volume is extraordinary. Baikal holds roughly 23,000–23,600 cubic kilometers (about 5,500–5,670 cubic miles) of freshwater. This equals around 20–23% of the world’s unfrozen surface freshwater in lakes and rivers. Put differently, you would need all the water from the five North American Great Lakes combined to roughly match Baikal’s volume. Even then, Baikal would still win.

The water is famous for its clarity, especially in winter when plankton activity is low. Under calm, cold conditions, underwater visibility can reach 130 feet (around 40 meters). In summer, when more algae bloom near the surface, transparency is smaller, but the water is still clearer than in most large lakes. High oxygen levels even in deep layers make Baikal different from many other deep lakes, which often have “dead zones” with little or no oxygen.

How Lake Baikal Formed: Rift Valley, Age & Geology

Rift Valley Setting and Age

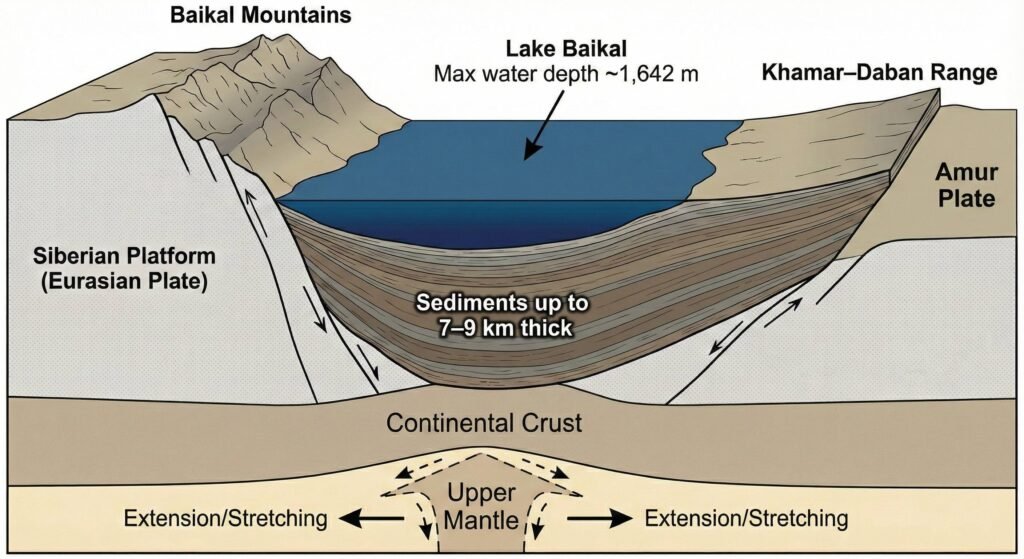

Lake Baikal sits in the Baikal Rift Zone, where the Earth’s crust is slowly pulling apart. This process has created a long, narrow depression similar to the East African Rift, but filled with freshwater instead of sea water. The rift is still active and widens by about 0.16 inches (4 millimeters) per year. That rate is slow on a human timescale but fast in geological terms.

Scientists estimate Baikal’s age at roughly 25–30 million years, making it one of the oldest known lakes. Most lakes are geologically young and disappear within a few tens of thousands of years as rivers fill them with sediment. At Baikal, however, the lake floor continues to sink while sediments fill in, so the basin survives. Under the lake bottom there are about 7 kilometers (over 4.3 miles) of sediment, which record millions of years of past climate and environmental change.

Seismic activity is another key feature of the rift. The region experiences frequent small earthquakes and occasional stronger ones. Hot springs around the lake hint at deeper heat and fluid circulation. For geologists, Baikal is a natural laboratory. It shows how continents stretch, how deep basins form, and how sediments store climate records that researchers can drill and read like a history book.

Climate, Seasons & Famous Ice of Lake Baikal

Temperatures, Ice and Climate Change

Siberia has harsh winters, and Baikal is no exception. The climate is strongly continental, with long cold winters and short cool summers. Around the lake, average January air temperatures often drop to about −2 to −4 °F (−19 to −20 °C), while July averages near the shore reach roughly 57 °F (14 °C). The huge water body slightly softens extremes, so coastal villages are usually milder than areas farther inland.

Baikal usually freezes between January and early February and stays ice-covered until May, sometimes into June in the north. In most places, clear ice grows to about 3.3–4.6 feet (1–1.4 meters) thick. Pressure ridges and hummocks can stack it to more than 6.5 feet (2 meters). In winter, strong winds polish and crack the ice, creating bright blue sheets with white fracture lines and frozen bubbles trapped underneath. These patterns have turned Baikal’s winter ice into an Instagram favorite and an important part of the local tourism economy.

Scientists pay close attention to Baikal’s ice because it responds to climate change. Long-term records show that surface waters have warmed and ice-cover timing has shifted in recent decades. Different studies highlight different time windows and trends. One famous 60-year dataset collected by a Siberian scientist family shows significant warming of surface waters, especially in summer, which affects plankton and fish. Newer work on Northern Hemisphere lake ice also uses Baikal as a key example when studying how ice seasons change in a warming world.

Wildlife of Lake Baikal: Endemic Species & Food Webs

Lake Baikal is often called the “Galápagos of Russia” because of its extraordinary biodiversity. Depending on the source and how groups are counted, scientists have recorded roughly 1,000 plant species and between 2,000 and 2,500 animal species in and around the lake. A very high share of these—often estimated at 50–80% for some groups—are endemic, meaning they exist nowhere else on Earth.

The food web starts with tiny photosynthetic algae and cyanobacteria, which use sunlight to grow in the upper water layers. Zooplankton such as copepods and cladocerans graze on this “green soup.” Small fish eat the zooplankton, larger fish eat the small fish, and seals and birds feed higher up the chain. Because the water is cold, clear and oxygen-rich, animals can live at great depths. Some Baikal fish and amphipods (a type of crustacean) spend their whole lives in water that is only a few degrees above freezing.

Baikal Seal (Nerpa): A Freshwater Specialist

The Baikal seal, or nerpa (Pusa sibirica), is the lake’s most iconic animal. It is one of the smallest true seals and the only seal species whose entire population lives in freshwater. Adults are usually 3.6–4.6 feet (1.1–1.4 meters) long and can weigh up to 154 pounds (70 kilograms).

Modern population estimates from IUCN and other research groups place the number of Baikal seals at around 80,000–100,000 animals. Researchers think this is close to the ecosystem’s carrying capacity. Female seals give birth in snow caves on top of the ice, where pups are hidden from the cold wind and predators. Seals feed mainly on small fish like golomyanka and on amphipods, helping maintain balance in the deep-water food web. For local people, nerpa has long been a source of fur and meat, so hunting is now regulated by quotas.

Fish, Sponges & Tiny Crustaceans

Baikal hosts more than 50 native fish species, and many of them are endemic. Omul, a whitefish, has played a key role in local diets and trade. Several sculpin species and the almost transparent golomyanka oilfish are adapted to deep, cold, dark conditions. Golomyanka gives birth to live young and can make up a large share of the lake’s fish biomass.

In shallow areas, green Baikal sponges form underwater “gardens” on rocks and wood. These sponges live with symbiotic algae that give them their color and help them grow. The lake also hosts hundreds of endemic amphipod species, some only a few millimeters long, others larger. They shred dead plant material, graze on algae and even prey on each other, playing a key role in recycling nutrients throughout the lake. Genetic studies continue to reveal new hidden species and lineages inside this miniature world.

People, Culture & History Around Lake Baikal

Indigenous Communities and Russian Expansion

Humans have lived around Lake Baikal for thousands of years. Archaeological finds and petroglyphs suggest that Indigenous groups used the shores long before written records. Today, the Buryat people—who have Mongolic roots and traditions connected with Buddhism and local shamanism—live mainly on the eastern side of the lake. They raise goats, cattle, sheep and horses on surrounding grasslands and often refer to Baikal as a sacred “Sea.”

Russian exploration of Baikal expanded in the 17th century, when Cossacks and traders moved east across Siberia. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway brought new towns, industry and tourism. The Circum-Baikal Railway along the southwest shore once formed a difficult but spectacular part of the main trans-continental route. Today, part of it serves as a scenic heritage line.

In the Soviet period, Soviet authorities built large industrial projects, including pulp and paper mills and power plants, near the lake and its outflow. These provided jobs but also triggered pollution and strong public debates. Environmental activism around Baikal played an important role in the development of Soviet and Russian green movements, and local NGOs still monitor the lake closely.

Environmental Pressures & Protection (as of 2025)

Climate Change at Lake Baikal

Despite its size and isolation, Lake Baikal is vulnerable to modern pressures. Climate-related changes include warming surface waters, altered ice seasons and shifts in plankton communities. Studies suggest that by 2100, summer and autumn surface temperatures could be more than 4.5 °C (8.1 °F) warmer than in the 20th century. This scenario assumes that high greenhouse-gas emissions continue. Such warming can influence the timing of plankton blooms, fish spawning and seal behavior.

Pollution and Conservation Actions

On the pollution side, the main problems are poorly treated wastewater from towns and tourist areas, solid waste on beaches, and past industrial discharges. In some bays, especially near settlements, mats of filamentous green algae such as Spirogyra have appeared in recent years. These blooms can smother native plants and invertebrates and indicate nutrient overloads. Researchers have also detected microplastics in some Baikal organisms, reminding us that global plastic waste reaches even remote lakes.

Protection efforts are strong but must keep pace with change. In 1996, UNESCO listed Lake Baikal as a World Heritage Site, recognizing its extraordinary biodiversity and scientific importance. Russian federal law grants the lake a special status, with zones that strictly limit industry, fishing and construction. Several national parks and nature reserves line the shores, and international scientists work with local authorities to track water quality, seal populations and climate trends. Continued funding, careful tourism management and stronger wastewater treatment will be essential to keep Baikal healthy for future generations.

FAQ

Lake Baikal Questions & Answers

Even though Lake Baikal is a specialist topic, many questions repeat in school projects and travel planning. This short FAQ covers the most common ones in simple language while keeping scientific accuracy.

Why is Lake Baikal considered the world’s deepest lake?

Baikal’s basin was formed by a continental rift that continues to sink over millions of years. As sediments fill in, the lake floor keeps dropping. The result is a maximum water depth of about 5,315–5,387 feet (1,620–1,642 meters), deeper than any other freshwater lake on Earth.

Is Lake Baikal the largest lake in the world?

By surface area, Baikal is not the largest; lakes like the Caspian Sea and Lake Superior are bigger. By volume of freshwater, however, Baikal is number one. It holds roughly 23,000–23,600 km³ (about 5,500–5,670 cubic miles) of water, which is more than the five Great Lakes of North America combined.

Can people drink water from Lake Baikal?

Historically, local people drank straight from the lake because the water is very clear and low in nutrients. In remote areas this is still common. For modern visitors, health agencies usually recommend boiling or filtering Baikal water before drinking, especially near towns. Local pollution can cause problems even in a very clean lake overall.

What animals live only in Lake Baikal?

The best-known endemic animal is the Baikal seal (nerpa), the only seal species living only in freshwater. Many fish, including numerous sculpins and the deep-water golomyanka, are also endemic. On top of that, hundreds of amphipod crustaceans, snails, worms and sponges exist nowhere else. This is why UNESCO calls Baikal one of the most biodiverse lakes on Earth.

How long is Lake Baikal frozen, and is it safe to walk or drive on the ice?

Baikal typically freezes from January to May. By mid-winter, ice thickness often reaches about 3.3–4.6 feet (1–1.4 meters), thick enough to support cars and even trucks on marked routes. However, there are always thin-ice zones near springs and cracks. Local authorities set official ice roads and warn visitors where travel is unsafe, so it is important to follow local guidance.

Why do scientists call Lake Baikal a natural laboratory?

Baikal combines great age, extreme depth, high oxygen levels and many endemic species. Its thick sediments store detailed climate records for millions of years, while its living communities show how life adapts to cold, deep, clear water. Because of this, limnologists, geologists, climate scientists and biologists all use Baikal to test ideas about evolution and environmental change.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Lake Baikal is located in southern Siberia and stretches 395 miles (636 kilometers) between mountain ranges in Russia.

- It is the world’s deepest freshwater lake and holds roughly one-fifth of global unfrozen surface freshwater.

- Baikal formed in an active continental rift that is still widening and sinking. About 7 kilometers (over 4.3 miles) of sediments lie beneath the lake floor.

- The lake supports thousands of plant and animal species, including the unique Baikal seal and many endemic fish and invertebrates.

- Climate change, pollution and tourism pressures are real. UNESCO World Heritage status and Russian protection laws aim to safeguard this “Galápagos of Russia” for the future.