The saltiest lakes in the world are hypersaline waters with salt levels far above the ocean’s 3.5% salinity, including Gaet’ale Pond in Ethiopia, Don Juan Pond in Antarctica, Lake Assal in Djibouti and the Dead Sea. Many are shrinking because rivers that once fed them are dammed or diverted for farms and cities while warmer, drier climates speed up evaporation.

What Is a Hypersaline Lake?

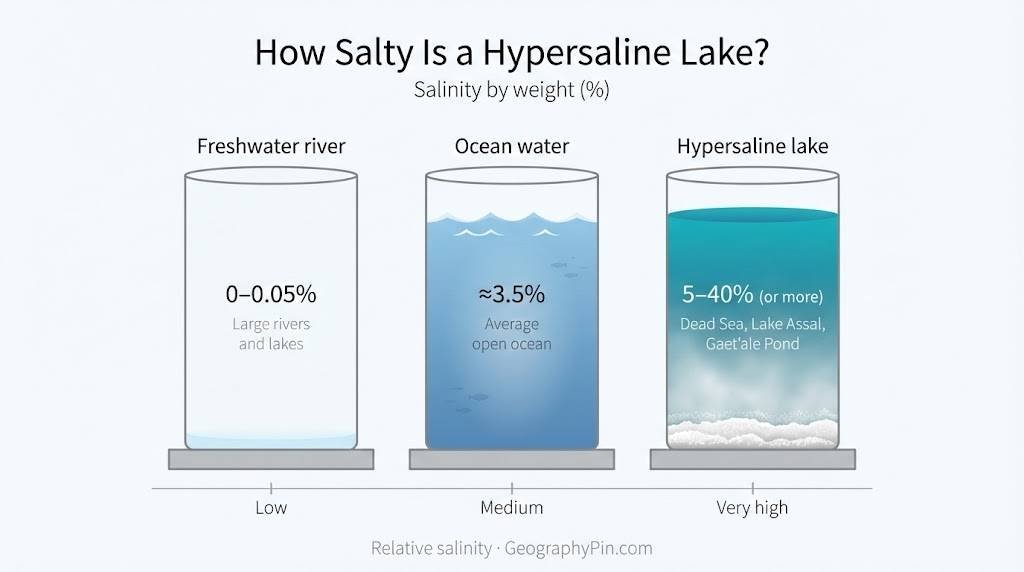

A hypersaline lake is any natural lake whose salinity is higher than typical seawater. Average ocean water contains about 3.5 grams of dissolved salt per 100 grams of water (3.5%), while hypersaline lakes can range from around 5% up to more than 40% salt. In this article we express salinity as percent by weight (%); some sources instead use grams per litre (g/L) or total dissolved solids (TDS), which is one reason you sometimes see slightly different numbers for the same lake. There is no single strict cut-off: some scientists call anything saltier than seawater “hypersaline”, while others reserve the term for very high levels above about 5%.

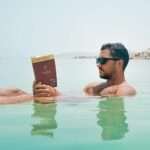

Most hypersaline lakes sit in “closed” inland basins in dry climates. Most hypersaline lakes are landlocked in arid regions where evaporation is stronger than inflow, so water leaves as vapour while salts stay behind. Classic examples include the Dead Sea between Jordan, Israel and the West Bank, where Dead Sea salinity reaches about 34%, Lake Assal in Djibouti, the Great Salt Lake in the United States and a cluster of tiny but ultra-salty ponds in Antarctica’s McMurdo Dry Valleys. Their chemistry varies: some are dominated by sodium chloride (table salt), others by calcium or magnesium salts, but all are concentrated enough to feel syrupy and to hold swimmers effortlessly on the surface.

How salty is “salty”? Benchmarks for lakes

Because salinity numbers can feel abstract, it helps to compare basic categories: freshwater, brackish water, normal seawater and truly hypersaline lakes. Values below are rough ranges by weight percent (grams of salt per 100 grams of water). Real lakes move up and down within these bands as rainfall, inflow and evaporation change from year to year.

| Water type | Typical salinity (% by weight) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Freshwater | 0–0.05% | Large rivers and most lakes used for drinking water |

| Brackish water | 0.05–3% | Estuaries where rivers meet the sea |

| Average ocean | ~3.5% | Open Atlantic or Pacific Ocean |

| Saline lake | 3.5–5% (can go higher during drought) | Mildly salty closed-basin lakes |

| Hypersaline lake | >5% up to ~40%+ | Dead Sea, Lake Assal, Gaet’ale Pond, Don Juan Pond |

In practice, an individual lake may slide between these categories from season to season. A wet year can push a hypersaline lake down toward the “saline” band, while a severe drought can concentrate it to the top end of the hypersaline range.

How Salt Lakes Form (and Why They Get So Salty)

Most salt lakes begin as ordinary lakes in “endorheic” basins – drainage basins with no outlet to the sea. Rivers and groundwater carry tiny amounts of dissolved minerals into these low spots. Because there is no river flowing out, the only way water can leave is by evaporating into the air, leaving its cargo of salts behind. Over thousands of years, this slow drip of minerals builds up into dense brines and thick layers of rock salt and gypsum. Those same salts later form the bright crusts and flats that tourists walk on and that can become dusty when lakes dry out, driving some of the problems described later in this article.

Climate is the second key ingredient. Hypersaline lakes thrive in hot, dry regions where evaporation is intense and rainfall is low. The Dead Sea, for example, lies about 1,300 feet (430 meters) below sea level in a desert zone that gets less than 4 inches (100 millimeters) of rain most years. Lake Assal in Djibouti sits 509 feet (155 meters) below sea level in one of the hottest places on Earth, while Utah’s Great Salt Lake occupies the dry Great Basin of western North America. Many of these lakes sit in rift valleys or volcanic depressions – like the Dead Sea graben, Lake Assal’s crater setting and the Danakil Depression – which form deep bowls that trap both water and salts.

Closed Basins: Water In, No Water Out

“Endorheic basin” is a technical way of saying “water comes in, but there is no river going out.” These closed basins are the natural homes of hypersaline lakes. Every drop of water that enters eventually has to leave as vapour, so whatever salt it carried stays behind in the basin.

Mono Lake in California, for example, sits in a high desert bowl east of the Sierra Nevada. Streams and groundwater flow down from the mountains, but there is no outlet river, so the lake is naturally salty. The Caspian Sea – the world’s largest enclosed inland body of water – is another huge endorheic system, with salinity lower than the ocean but still high enough to classify as a saline basin. Smaller lakes all around Central Asia, Iran and western China follow the same pattern.

This simple “bathtub with no drain” logic explains why closed basins are so sensitive to changes upstream. If humans remove more water for farms and cities, or if warmer air dries the region, water levels fall and salinity spikes. That is exactly what we see today at places like Great Salt Lake, Lake Urmia and many smaller saline lakes across the dry belts of the world.

Minerals, microbes and pink lakes

As brines concentrate, different minerals “drop out” at different stages. Common salt (halite) may form bright white crusts, while gypsum and other evaporite minerals build patterned flats around a lake’s edge. In some lakes, salt-loving algae and microbes, such as Dunaliella and certain archaea, produce red and orange pigments. That is why parts of Senegal’s Lake Retba and the north arm of the Great Salt Lake often look pink or brick-red from the air.

These minerals and microbes are not just pretty. Evaporite deposits around ancient salt lakes record past climate swings in their layers. Microbial mats at the edges of modern hypersaline lakes provide models for early Earth ecosystems, when large parts of the planet’s surface water may have been much saltier than today. When these delicate crusts are broken by vehicles, construction or heavy tourist traffic, they can take decades to recover, and once the crust is gone it can be more easily lifted into the air as dust.

Ranking the Saltiest Lakes in the World

Ranking the “saltiest” lakes is trickier than it sounds. Salinity changes with seasons, droughts and human water use, and measurements are not always made in the same way. Still, scientists keep a rough league table of hypersaline waters. Very small ponds like Gaet’ale in Ethiopia and Don Juan in Antarctica sit near the top, followed by Lake Assal, Lake Retba, the Dead Sea and parts of the Great Salt Lake, along with several lesser-known salt lakes in Russia, Iran and Central Asia. Tiny ponds such as Gaet’ale and Don Juan are currently the saltiest natural waters measured on Earth; larger lakes like the Dead Sea and Lake Assal follow behind them.

The table below pulls together widely cited maximum salinity values from scientific papers and reference compilations. Remember that these are approximate peak values; in wet years, many of these lakes may be far less salty, while in intense drought they can briefly exceed these numbers. A final “Trend / Status” column connects the trivia (how salty) with the bigger story (which lakes are in trouble).

| Lake / Pond | Country / Region | Approx. max salinity (%) | Type | Notable features | Trend / Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaet’ale Pond | Ethiopia (Danakil Depression) | ~43% | Volcanic spring pool | Often cited as the saltiest natural water body on Earth; fed by hot, CO₂-rich springs. | Very small; water level and chemistry fluctuate with geothermal activity. |

| Don Juan Pond | Antarctica (McMurdo Dry Valleys) | ~40–45% | Hypersaline pond | Remains liquid at about -58°F (-50°C) thanks to calcium-chloride brine; a key McMurdo Dry Valleys Mars analog site. | Tiny but stable; controlled by local melting and brine flow. |

| Lake Retba | Senegal | Up to ~40% | Coastal dune lake | Known as the “Pink Lake” for its colour from halophilic algae; heavily mined for salt. | Salinity and water level vary with rainfall and salt extraction; localised pressure. |

| Lake Elton | Russia (Caspian lowlands) | 20–35% (can exceed in extreme drought) | Shallow steppe lake | Extremely variable salinity; long history of therapeutic mud and salt extraction. | Highly variable; sensitive to climate and extraction. |

| Lake Assal | Djibouti | ~34.8–40% | Crater / rift lake | Lowest point in Africa at -509 ft (-155 m); about ten times saltier than the ocean. | Small but economically important; slowly receding with industrial use and warming. |

| Dead Sea | Jordan / Israel / West Bank | ~34% | Rift valley lake | Deepest hypersaline lake on Earth, with shores about 1,300 ft (430 m) below sea level. | Water level dropping quickly due to river diversion and mineral extraction. |

| Great Salt Lake, North Arm | USA (Utah) | Up to ~31–32% | Terminal basin lake | Separated by a causeway; northern arm can approach Dead Sea–like salinity. | Part of a lake that has lost around three-quarters of its volume vs 1980s highs; crisis status. |

| Deep Lake | Antarctica | ~27% | Coastal Antarctic lake | Stays unfrozen to depth despite Antarctic winters; supports specialised microbes. | Remote and relatively stable but sensitive to long-term climate change. |

| Lake Urmia | Iran | ~8–28% | Endorheic salt lake | Once the largest lake in the Middle East; has shrunk dramatically since the 1990s. | Shrunk to roughly 10% of its 1970s area; partial restoration efforts underway. |

| Garabogazköl Aylagy | Turkmenistan (Caspian Sea gulf) | ~30–35% | Shallow lagoon | Hyper-saline gulf periodically cut off from the Caspian; major source of industrial salts. | Water level and salinity swing with Caspian levels and canal management; ecologically stressed. |

| Mono Lake | USA (California) | ~8–13% | High desert lake | Known for limestone “tufa” towers and millions of migratory birds. | Salinity peaked after heavy water diversions; partial recovery since legal protections restored inflows. |

Different years and measurement methods give slightly different salinity values for each lake, so you should treat these figures as best-available maximum estimates rather than exact, fixed numbers.

Dead Sea vs Great Salt Lake vs Lake Assal – Who Wins?

Three famous salt lakes often compete in headlines: the Dead Sea, Great Salt Lake and Lake Assal. By maximum salt concentration, Lake Assal usually edges out the Dead Sea, with average salinity around 34.8% and up to 40% at depth, compared with about 34% for the Dead Sea and up to around 31–32% for the north arm of Great Salt Lake. Many popular lists that call the Dead Sea “the saltiest lake in the world” are focusing only on large lakes and ignoring tiny hypersaline ponds like Gaet’ale or Don Juan, which is why rankings sometimes look inconsistent.

| Lake | Surface area (approx.) | Max depth (approx.) | Typical salinity | Overall trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead Sea | Now ~234 sq mi (605 km²); mid-20th century ~405 sq mi (1,050 km²) | ~997 ft (~304 m) | ~34% | Shrinking quickly; water level dropping by roughly 3 ft (~1 m) per year in some periods. |

| Great Salt Lake (whole) | Historic high ~3,300 sq mi (8,500 km²); record low ~950 sq mi (2,460 km²) | Mostly <35 ft (<11 m) | South arm often ~12–17%; north arm up to ~31–32% | Lost around 73% of water volume vs 1980s highs; recent partial rebound but still in crisis. |

| Lake Assal | ~21 sq mi (~54 km²) | >130 ft (>40 m) | ~34.8–40% | Small but economically important; slowly receding with industrial use and warming. |

In area and depth, the Dead Sea is the heavyweight. Its surface covers roughly 234 square miles (605 square kilometers) today, and the deepest point reaches around 997 feet (304 meters). Great Salt Lake, at historic highs, covered about 3,300 square miles (8,500 square kilometers) but is generally shallow, mostly under 35 feet (11 meters) deep. Lake Assal is much smaller, with a surface area similar to a medium-sized city and a depth only a fraction of the Dead Sea’s.

Only the isolated north arm of Great Salt Lake reaches Dead Sea–like salinity. A railroad causeway limits the mixing of fresh water into this arm, so salt builds up there, while the larger south arm remains less salty but still far above ocean levels. This split between the Great Salt Lake arms is one reason different sources quote different salinity values for the “same” lake.

Hidden Hypersaline Lakes Under Ice

Not all extreme salt lakes sit in hot deserts. In Antarctica and the Arctic, some brine lakes hide under ice or nestle in nearly rainless valleys. Don Juan Pond and Lake Vanda in Antarctica’s McMurdo Dry Valleys are so salty that they stay liquid at temperatures far below freezing. Their brines contain unusual mixes of calcium and chloride ions, and their chemistry and conditions have made them important analogs for possible salty brines on Mars.

Under ice caps, things get even more mysterious. Radar and other geophysical surveys have identified a complex of likely hypersaline subglacial lakes and brine-saturated sediments beneath Canada’s Devon Ice Cap, covering roughly 9.5 square miles (about 25 square kilometers) and linked by a larger network of salty groundwater. These hidden lakes appear to be kept liquid by pressure and salt rather than heat, and could host specialised microbial life despite permanent darkness and sub-zero temperatures. Because of this, scientists working on Mars rovers and future missions to icy moons such as Europa and Enceladus use these icy brine systems as training grounds and comparison sites.

Life in “Impossible” Lakes

At first glance, it looks like nothing could survive in water so salty that fish die within minutes. Yet many hypersaline lakes are full of microscopic life. Salt-loving archaea and bacteria, often grouped under the nickname “halophiles,” have adapted cell membranes and proteins that keep working even when salt concentrations would destroy ordinary cells. Some produce bright red or orange pigments that help protect them from intense sunlight and contribute to the colours of pink lakes and the north arm of Great Salt Lake.

In moderately hypersaline lakes, larger organisms also thrive. Great Salt Lake supports vast populations of brine shrimp and brine flies, which in turn feed millions of migrating birds such as grebes, phalaropes and avocets. Mono Lake plays a similar role for birds crossing the North American flyways, and many other saline lakes act as stepping stones for global migrations.

In some cases, halophilic microbes and their enzymes are used in biotechnology, for example in salt-tolerant industrial processes or as natural colourants. For astrobiologists, these ecosystems show how life can adapt to extremes of salt, temperature and dryness – conditions similar to those suspected on Mars or the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

Why the World’s Salt Lakes Are Shrinking

Across the planet, many salt lakes are losing water much faster than in the past. The main driver almost everywhere is human water use. Rivers that once fed these lakes are now heavily dammed and diverted for irrigation, industry and cities. The Aral Sea, once a vast inland sea in Central Asia, has shrunk to less than 10% of its original area since the 1960s after the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers were diverted for cotton fields.

There are some partial success stories. In the 1990s and 2000s, a dam project on the northern part of the Aral Sea, combined with better river management, allowed the “North Aral Sea” to regain some water and fish. Mono Lake began to recover after court rulings forced Los Angeles to reduce its water diversions, showing that when inflows are legally restored, a salt lake can at least partly bounce back.

Lake Urmia in Iran tells a more fragile story. It was once about 5,000–6,000 square miles (13,000–16,000 square kilometers) in area, making it the largest lake in the Middle East. By the late 2010s it had shrunk to roughly 10% of that size, and satellite images now show that much of the basin is exposed salt flats. A combination of dam building, groundwater pumping, road causeways and recurring drought has pushed the lake toward collapse and has dramatically increased its salinity.

Climate change amplifies these pressures. Warmer air increases evaporation from already dry basins and can shift rainfall patterns away from lake catchments. In the American West, a warming climate and long-term drought, combined with water diversions, helped drive Great Salt Lake to a record low elevation in 2022, with surface area dropping to around 950–1,000 square miles (2,460–2,590 square kilometers). One widely cited study estimated that roughly two-thirds of its long-term water loss comes from human consumption, with climate-driven drought making up the rest. For the Aral Sea and Lake Urmia, large-scale irrigation projects are the main driver, while climate acts as a stress multiplier rather than the original cause.

- Human drivers: dams and canals that trap rivers, large irrigation schemes, city and industrial withdrawals, and intensive groundwater pumping that starves lakes of inflow.

- Climate drivers: warming temperatures that boost evaporation, multi-year droughts, and shifts in rainfall that reduce the water reaching endorheic basins.

Zooming out, researchers who have reviewed saline lakes worldwide find a clear pattern: a large majority of the world’s major salty lakes have already lost a big share of their surface area, often around half, in just a few decades. In many regions, shorelines have retreated kilometres, exposing wide belts of salt flats and mud.

Taken together, these losses show that what is happening at the Dead Sea or Great Salt Lake is not a local oddity but part of a global shift in how we use and mismanage water in closed basins. The same combination of river diversions and a warming climate plays out from Central Asia to the Middle East, North America and Australia.

| Lake | Peak size (approx.) | Recent low (approx.) | Main human drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aral Sea | ~26,000 sq mi (67,000 km²) | <10% of original area | Massive irrigation diversions for cotton and other crops |

| Lake Urmia | ~5,000–6,000 sq mi (13,000–16,000 km²) | Down to a few hundred sq mi (<1,000 km²) by the 2010s–2020s | Dams, groundwater pumping, irrigation, causeway construction |

| Great Salt Lake | Up to ~3,300 sq mi (8,500 km²) | Record low ~950 sq mi (2,460 km²) in 2022 | River diversions, agriculture, urban growth, warming climate and drought |

| Dead Sea | ~405 sq mi (1,050 km²) in mid-20th century | ~234 sq mi (605 km²) in recent decades | Upstream diversions, mineral extraction, reduced river inflow |

What Happens When a Salt Lake Collapses?

When a salt lake shrinks, the lakebed does not stay quiet. Wind picks up fine, salty sediments and blows them across nearby towns and farms. In Central Asia, dust from the dried Aral Sea has carried salt and agricultural chemicals hundreds of miles, contributing to higher rates of respiratory disease, cancers and other health problems. Similar “salt storms” now affect communities around Lake Urmia and other drying lakes on the Iranian Plateau. Around Great Salt Lake, exposed lakebed contains naturally occurring arsenic and other metals, and dust clouds from the dry playa increasingly reach a metro area of more than 2 million people along the Wasatch Front. At the Dead Sea, rapid shoreline retreat has triggered sinkholes that threaten roads and tourist infrastructure, and the loss of water harms wildlife from brine shrimp and fish to millions of birds that rely on these lakes as rest stops on migration routes.

These health burdens and disruptions often fall hardest on rural, Indigenous or lower-income communities who live closest to the dried lakebed and have the least ability to move away. Farmers downwind from the Aral Sea and Lake Urmia, for example, cope with salty dust settling on their fields, while residents around Great Salt Lake worry about long-term lung and heart impacts but may lack the resources to relocate. That makes collapsing salt lakes not just an ecological issue, but a clear environmental justice problem.

Visiting Hypersaline Lakes Safely

Despite the environmental worries, hypersaline lakes remain important travel destinations. Visitors float easily in the Dead Sea, watch flamingos at salty lagoons, walk on the blinding white salt flats of Lake Assal or explore viewpoints over the Great Salt Lake. For many travelers, the Dead Sea, Great Salt Lake and Lake Assal are the best-known hypersaline destinations. If you plan a visit, treat these places as both fragile ecosystems and powerful natural forces. Simple habits can keep you safe while reducing your impact.

First, protect your skin and eyes: avoid shaving or waxing for at least 24 hours before getting in, because even tiny cuts will sting badly in 30–35% brine. Never dive or splash, and keep your head above water; if salty water gets into your eyes, rinse immediately with plenty of fresh water. Limit your time in very salty water to around 10–20 minutes, especially for children, and keep kids away from deep or wave-exposed sections.

- Don’t wear contact lenses in the water, because a single splash of brine trapped behind a lens can be extremely painful.

- Don’t keep metal jewellery on for long salty baths, as high salinity can tarnish or damage some metals.

- Don’t let children put salty hands or water in their mouth; the brine tastes awful and can upset the stomach.

Second, respect local rules and wildlife. On shore, stay on marked paths, do not remove crystals or scrape salt crusts, and follow signs that protect nesting birds and fragile bacterial mats. In some places, such as sensitive wetlands around Great Salt Lake or the shrinking shores of Lake Urmia, authorities may close certain areas or limit access seasonally. In very hot, low-lying places like the Dead Sea and Lake Assal, carry plenty of drinking water, wear sun protection and watch for signs of heat stress.

FAQ

Which lake is currently the saltiest in the world?

Very small ponds, not big lakes, currently top the charts. Gaet’ale Pond in Ethiopia and Don Juan Pond in Antarctica both reach salinities around or above 40–43%, roughly twelve times saltier than the ocean. They are much smaller than the Dead Sea or Great Salt Lake but far more concentrated.

Is the Dead Sea really “dying”?

The water is already so salty that almost no fish or plants live in it, which is why it is called the Dead Sea. The real concern today is that its water level is falling quickly because inflow from the Jordan River has been diverted and minerals are extracted. As the shoreline retreats, sinkholes open and coastal ecosystems and infrastructure are stressed.

Can fish or larger animals live in hypersaline lakes?

In the saltiest lakes, like the Dead Sea or Lake Assal, fish cannot survive. However, some “moderately” hypersaline lakes support brine shrimp, brine flies and specialised microbes, which then feed birds. Great Salt Lake, for example, supports huge flocks of migratory birds that feed on brine shrimp and flies along its shores.

Why do some salt lakes look pink or red?

Pink and red colours usually come from salt-loving algae and microbes that produce protective pigments. When salinity and temperature reach the right range, these organisms bloom, staining the water. Lake Retba in Senegal and parts of Great Salt Lake are famous examples, and similar colours sometimes appear in evaporation ponds near the Dead Sea.

Can we “save” shrinking salt lakes?

In principle yes, but it requires tough choices. The most effective solution is to send more water back into the lake by reducing upstream withdrawals and improving irrigation efficiency. In practice, that means changing farming practices, limiting groundwater pumping and sometimes redesigning dams and canals. Climate mitigation also matters, because a hotter world evaporates more water from every shallow lake.

Why are so many of the world’s saltiest lakes disappearing now?

Most of today’s crises are driven by human water use: rivers have been dammed and diverted to feed crops, industries and growing cities, starving lakes of fresh inflow. Climate change then adds a second push by raising temperatures and intensifying droughts, which increases evaporation. Together, these forces can drain even very salty lakes in just a few decades and turn them into dusty salt flats.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Hypersaline lakes form where water flows in but not out, and evaporation concentrates salts far beyond ocean levels.

- The saltiest known waters today include tiny ponds like Gaet’ale and Don Juan, plus larger lakes such as Lake Assal and the Dead Sea.

- Many salt lakes are shrinking fast because rivers are dammed and diverted, while a warming climate boosts evaporation and drought.

- Desiccating lakebeds can unleash toxic dust storms, damage agriculture and erase key habitats for birds and other wildlife, often hitting nearby low-income communities hardest.

- Travelers can still enjoy these lakes safely by protecting their skin and eyes and respecting simple environmental rules and local regulations.