Tundra vs Taiga: Key Landscape Differences

Tundra is a cold, mostly treeless biome with frozen ground (permafrost) and short growing seasons, found at high latitudes and high elevations. Taiga, or boreal forest, is a belt of coniferous forest just south of the tundra, with taller trees, deeper soils, and slightly warmer, longer summers that support more biodiversity.

1. Tundra and Taiga on the Map: Where Each Biome Lives

Tundra and taiga wrap around the top of the Northern Hemisphere like two stacked rings. The tundra forms the upper ring, closest to the Arctic Ocean and the ice caps, while the taiga sits just below it. You can think of tundra as the “treeline zone” and taiga as the “northern forest belt.”

Arctic tundra stretches across northern Alaska, northern Canada, Greenland’s coastal fringe, northern Scandinavia, and northern Russia. Alpine tundra appears on high mountain tops in regions such as the Rockies, Andes, and Himalayas, where altitude replaces latitude. Taiga, meanwhile, covers huge parts of inland Canada and Alaska and runs across Scandinavia and Russia from about 50°N to 70°N, making it the world’s largest land biome by area as of 2025.

If you were to hike north from a town like Fairbanks, Alaska, or from central Finland, you would start in dense coniferous forest, then notice shorter, more widely spaced trees, and finally reach low, shrub-covered ground with almost no trees at all. That gradual shift is the taiga–tundra transition, also called the forest–tundra ecotone or the treeline.

Biome at a Glance: Tundra vs. Taiga

This comparison table summarizes the core differences between tundra and taiga that matter most if you are trying to identify them in the field, in photos, or on satellite images.

| Feature | Tundra | Taiga (Boreal Forest) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Latitude | Mostly above ~60°N or at high mountain elevations | Roughly 50°N–70°N in North America and Eurasia |

| Tree Cover | Treeless or scattered dwarf shrubs; no tall forests | Dense coniferous forests of spruce, pine, fir, larch |

| Climate Type | Polar/ET climate: very cold, short cool summer | Subarctic climate: long cold winter, short mild summer |

| Ground Conditions | Permafrost common, shallow active layer, often wet | Deeper, often acidic soils; permafrost only in coldest areas |

| Typical Summer High | Around 37–54 °F (3–12 °C) | Around 59–68 °F (15–20 °C) in many regions |

| Typical Winter Low | Often below −22 °F (−30 °C), can plunge lower | Commonly between −4 °F and −40 °F (−20 °C to −40 °C) |

| Precipitation | Low, roughly 6–10 in (150–250 mm) per year | Moderate, around 12–30 in (300–750 mm) per year |

| Vegetation Style | Mosses, lichens, sedges, dwarf shrubs | Tall conifers with some birch, aspen, willow |

| Biodiversity | Relatively low, highly specialized species | Higher than tundra, more plant and animal species |

2. Climate and Seasons: Frozen Ground vs. Snowy Forests

The easiest scientific way to separate tundra from taiga is to think about the ground and the seasons. In tundra, the key word is permafrost. This is soil that stays frozen year-round, sometimes for hundreds of feet (tens of meters) below the surface. Only a thin “active layer” thaws in summer, often just 4–40 in (10–100 cm) deep, which severely limits root growth and drainage.

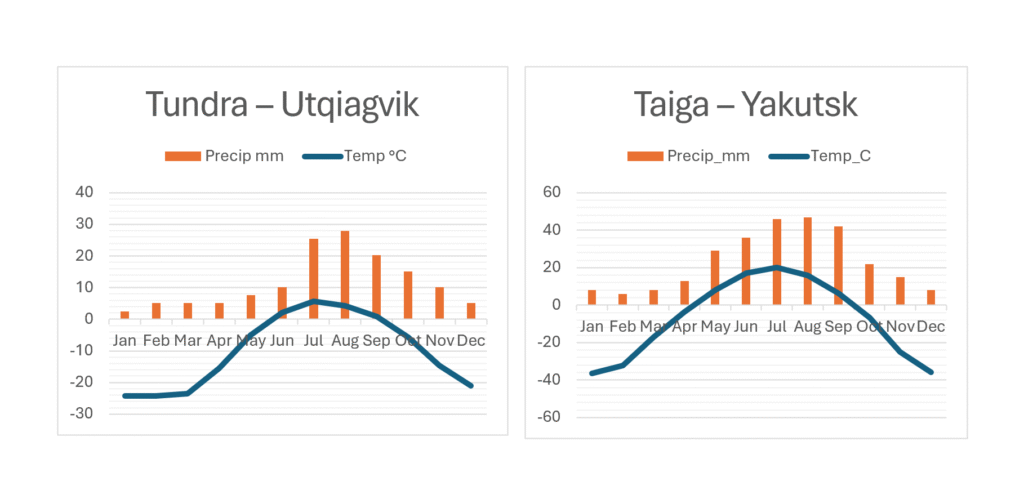

Because of permafrost and high latitude, tundra has very short growing seasons. Many areas have only 50–70 frost-free days per year. Winters are long, dark, and bitter, with air temperatures frequently below −22 °F (−30 °C). Summers can feel surprisingly mild in the sun, sometimes reaching 50–59 °F (10–15 °C), but the warmth does not last long enough for tall trees to mature.

Taiga has harsh winters too, but with important differences. The climate is subarctic rather than polar, with a bigger contrast between seasons. Winter can still drop to −40 °F (−40 °C), yet summers are warmer and longer than in tundra, often with average highs around 59–68 °F (15–20 °C) for 2–4 months. Snow can pile up several feet (over a meter) deep in winter, acting as a protective blanket for tree roots.

Precipitation also separates the two biomes. Many tundra areas receive only 6–10 in (150–250 mm) of precipitation per year, similar to dry steppe or semi-desert, but the cold prevents rapid evaporation. Taiga usually gets more moisture, around 12–30 in (300–750 mm) annually, enough to support dense forests and bogs. In both biomes, most of this water arrives as snow, but taiga also sees frequent summer rain.

Light, Day Length, and the Human Experience

Both tundra and taiga lie in high latitudes, so they share dramatic changes in daylight. In summer, the sun can shine for 20–24 hours per day north of the Arctic Circle, creating the “midnight sun.” In winter, days can shrink to only a few hours of dim light or full polar night.

However, the way the land responds is different. In taiga, long summer days help trees push out new needles, grow wood, and store carbohydrates. In tundra, the same daylight launches a rush of growth from low plants, but the shallow active layer and cold soil keep productivity lower overall. For Indigenous peoples, reindeer herders, and forest communities, these differences shape everything from migration routes to building design.

3. Plants, Animals, and Soil: What the Landscape Looks and Feels Like

Look at the ground, and you will see the clearest visual difference between tundra and taiga. Tundra is mostly treeless. The tallest plants are usually dwarf shrubs, perhaps 8–24 in (20–60 cm) high, spread across a patchwork of mosses, lichens, sedges, and small flowering plants. In summer, it turns into a colorful carpet close to the soil; in winter, it is a windswept snowfield with plants hidden under the surface.

Taiga, by contrast, is dominated by coniferous trees: spruce, pine, fir, and larch. Many of these trees grow 30–80 ft (9–25 m) tall, sometimes more. Their narrow, pointed crowns and sturdy branches help them shed snow. Some broadleaf trees like birch and aspen appear, especially toward the southern edges of the taiga, giving the forest a mixed look in autumn when leaves turn yellow and orange.

Animals differ too. Tundra wildlife includes caribou (reindeer), Arctic foxes, lemmings, musk oxen, and birds like snowy owls and Arctic terns. These species are highly adapted to cold, open spaces and seasonal food bursts. Taiga supports large mammals such as moose, brown bears, wolves, lynx, and many species of songbirds and woodpeckers. The forest structure offers more hiding places, nesting sites, and varied food.

Underfoot, soils tell another part of the story. Tundra soils are thin, often waterlogged in summer, and sit atop permafrost. They can store huge amounts of organic carbon locked in frozen peat. Taiga soils are deeper but often acidic due to needle litter. Thick layers of organic material build up, and in many places, deep peatlands and bogs form, storing vast quantities of carbon in wet conditions.

Field Checklist: How to Tell Tundra from Taiga Quickly

When you are outdoors or looking at photos, this quick checklist helps you decide if you are seeing tundra or taiga:

- Tree height and density: Almost no tall trees suggests tundra; continuous forest of conifers suggests taiga.

- Ground texture: Spongy, wet ground with many small plants and shallow ponds often indicates tundra; a floor of needles, moss, and fallen branches points to taiga.

- Snow behavior: In taiga, snow stacks on branches and logs; in tundra, wind scours snow across open ground.

- Human land use: Taiga areas are more likely to host logging roads, small towns, and power lines. Tundra regions tend to have fewer permanent structures and more seasonal camps.

FAQ

How can I quickly tell tundra and taiga apart in a photo?

Look at the trees first. If you see a dense forest of tall conifers like spruce and pine, you are probably looking at taiga. If trees are missing or only tiny shrubs are present, and the ground looks open and low, it is likely tundra. The overall feel is “forest” versus “open plain.”

Does tundra always have permafrost while taiga does not?

Tundra is strongly associated with permafrost, and many Arctic tundra areas have permanently frozen ground just below the surface. Taiga can have permafrost in its coldest northern parts, especially in Siberia and Alaska, but much of the taiga sits on seasonally frozen but not permanently frozen soil.

Which biome stores more carbon: tundra or taiga?

Both store huge amounts of carbon, but in different ways. Tundra holds vast carbon reserves in frozen permafrost soils. Taiga stores large amounts in its forests and peatlands. As of 2025, scientists are especially concerned about tundra permafrost thawing and releasing carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere.

Are there tundra and taiga in the Southern Hemisphere?

There is no large belt of taiga in the Southern Hemisphere, mainly because there is less land at the right latitudes. However, tundra-like conditions exist on high mountains and in parts of Antarctica’s coastal regions, where cold, dry conditions prevent tree growth.

Why are tundra and taiga important for climate change?

These biomes act as major climate regulators. They store enormous amounts of carbon in trees, soils, and permafrost. When tundra permafrost thaws or taiga forests burn, some of this stored carbon is released as greenhouse gases, which can speed up global warming and further change these ecosystems.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Tundra is a cold, mostly treeless biome with permafrost and very short growing seasons.

- Taiga is a subarctic coniferous forest biome and is the largest land biome on Earth.

- Climate and ground conditions—especially permafrost—strongly shape which plants and animals can live in each biome.

- From the air or on the ground, tree height and density are the fastest visual clues to tell tundra from taiga.

- Both biomes store vast amounts of carbon, so changes in tundra and taiga have global climate impacts as of 2025.