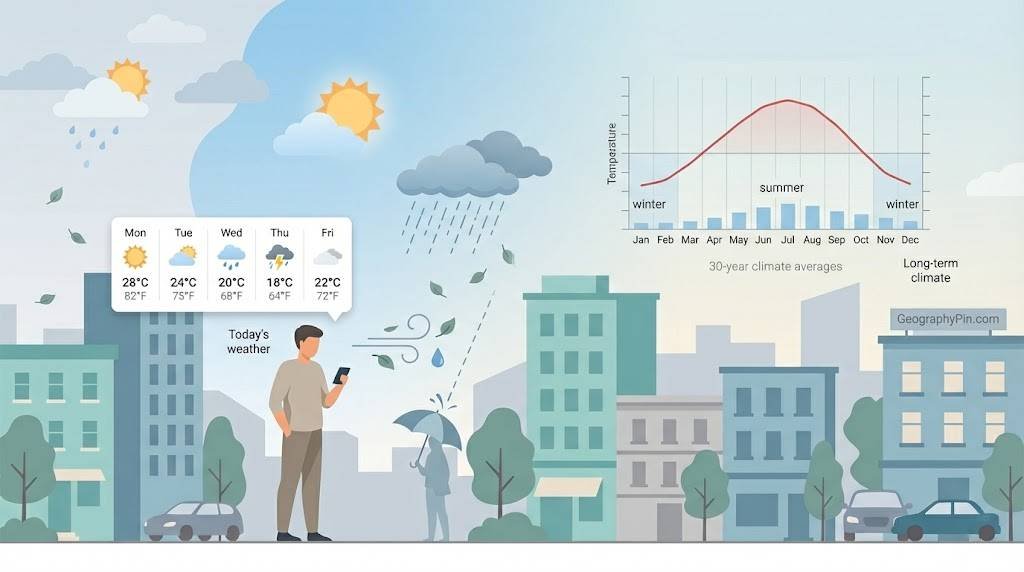

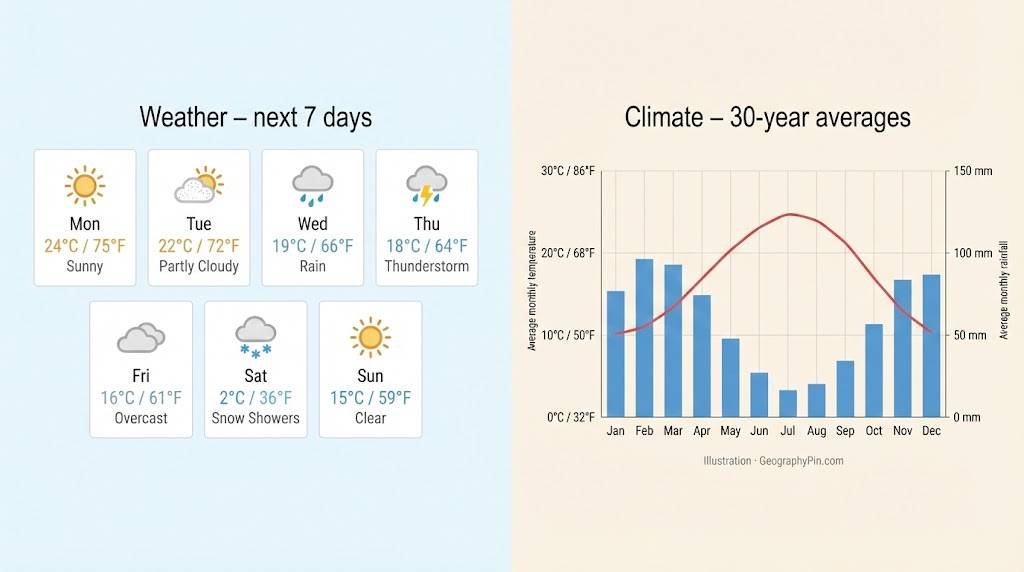

Weather is the short-term condition of the atmosphere in a specific place, over minutes to days. Climate is the long-term pattern of weather in a region, based on 30+ years of data, showing its typical conditions and extremes.

Weather vs Climate: The Basic Definitions

Weather describes what the air is doing right now or in the very near future at a specific place. It covers fast changes that can happen within minutes or hours, such as a rain shower starting, fog forming, or the wind suddenly picking up before a storm.

Climate describes the long-term pattern of weather in a region. Scientists usually look at at least 30 years of data to define climate so they can see the typical conditions and the range of extremes, such as how hot summers usually get or how cold rare cold snaps can be.

Weather is what you get today; climate is what you usually get over many years. Put simply, weather is a snapshot, and climate is the long-running movie.

Weather vs Climate: Side-by-Side Comparison

Both weather and climate are built from the same basic ingredients: temperature, precipitation, humidity, wind, air pressure, and cloud cover. These ingredients describe what the atmosphere is doing.

They use the same ingredients but on different time and space scales. Weather tracks hour-to-hour and day-to-day changes in a specific place, while climate looks at patterns across decades and across larger regions.

| Aspect | Weather | Climate |

|---|---|---|

| Time scale | Minutes to about 10–14 days | At least 30 years, often decades to centuries |

| Space scale | Street, city, or region | Region, country, or whole planet |

| Typical question | “Will it rain this afternoon?” | “How rainy are winters here on average?” |

| Science field | Meteorology | Climatology |

| Examples | A thunderstorm at 3 p.m., foggy morning commute | Tropical monsoon climate, polar climate, Mediterranean climate |

| Use in daily life | Planning trips, sports, farming tasks this week | Designing buildings, choosing crops, planning water systems |

Microclimate describes small local climate differences inside a larger region. A city center can be a few degrees warmer than nearby countryside, or a shady valley can stay cooler and wetter than surrounding hills. It is still climate, just on a smaller scale, based on long-term patterns in that tiny area.

What Is Weather? Short-Term Changes in the Atmosphere

Weather is the mix of conditions you feel when you step outside today.

It includes the temperature of the air, whether it is dry or humid, if the sky is clear or cloudy, and whether water is falling as rain, snow, sleet, or hail. Weather also includes how strong the wind is and from which direction it is blowing.

Meteorologists study weather using weather stations, satellites, radar, and computer models. They gather data from the ground, from aircraft, and from space to build forecasts for the next few hours and days. Most public forecasts cover the next 1–7 days, because beyond about 10–14 days the atmosphere becomes very hard to predict in detail.

Real-Life Weather Examples

If a cold front passes over your town this evening, you might feel the temperature drop from 77°F (25°C) to 59°F (15°C) in a few hours. A line of showers and gusty winds follows the front. This sudden change is weather. Tomorrow, the wind may calm and the sky may turn clear again.

Another example: a summer thunderstorm that drops 1 inch (about 25 millimeters) of rain in 30 minutes over your neighborhood. The storm brings thunder, lightning, and strong gusts of 40 miles per hour (about 65 kilometers per hour). It may even hail for a few minutes. All of this is still just weather – short, sharp events.

Meteorology: The Science of Weather

Meteorology is the science that focuses on weather and the physics of the atmosphere in the short term, usually the next few hours and days. Meteorologists work in national weather services, airports, TV studios, and research centers. They use equations of fluid motion and thermodynamics, but they translate results into simple messages like “bring a jacket” or “expect thunderstorms after 4 p.m.”

Good weather forecasts can save lives, especially when it comes to hazards such as hurricanes, blizzards, heatwaves, or flash floods. Knowing when strong winds or heavy rain will arrive helps communities prepare, close schools or roads, and protect people living in exposed areas.

What Is Climate? Long-Term Patterns and Climatology

Climate describes the typical weather in a place over a long time. To define climate, scientists usually use at least 30 years of measurements.

This long period smooths out odd years, like one unusually cold winter or one extremely hot summer. It shows the pattern of seasons and the range of conditions that people, plants, and animals can usually expect.

For example, the Sahara Desert has a hot, dry climate. Many places there receive less than 4 inches (about 100 millimeters) of rain per year. In contrast, a tropical rainforest climate might receive more than 79 inches (about 2,000 millimeters) of rain annually. Places with a Mediterranean climate, such as parts of coastal California or southern Europe, have dry, warm summers and cooler, wetter winters.

Climatology is the science that studies these long-term patterns and how they change. Climatologists look at statistics, such as average temperature in July, the number of frost days in a year, or how often severe storms occur. They also use climate models to explore how rising greenhouse gas levels are likely to change future patterns. That’s why one strange month or one snowy winter does not mean the climate has changed. Climate is built from many years of data, not a single season.

Climate Normals and Records

To describe climate, scientists use both normals and records. Normals are average values, often from a 30-year span, such as “average January high is 41°F (5°C)”. Records describe extremes, such as “record high of 104°F (40°C)” or “record one-day rainfall of 3 inches (about 75 millimeters)”.

Both normals and records matter. Normals help people plan housing, farming, roads, and energy systems. Records show what the atmosphere is capable of, even if such events are rare. When records are broken again and again in a short period, it can be a sign that the climate itself is shifting.

Meteorology vs Climatology

It helps to remember that meteorology looks mostly at short-term events, while climatology looks at patterns over long periods. Meteorologists answer questions like “Will it rain this weekend?” or “Will there be frost tonight?” Climatologists answer questions like “How have winters changed over 50 years?” or “Are heatwaves becoming more common in this region?”

Both fields share tools such as satellites and computer models, but they use them differently. For example, a meteorologist might run a model to forecast a storm over the next 3 days. A climatologist might run a similar model many times to understand how storms might change in a world that is 3.6°F (2°C) warmer.

Everyday Analogies: Outfit vs Personality

Two simple analogies can make the difference clear. First, think of weather as your outfit and climate as your wardrobe. What you wear today depends on today’s forecast. The clothes you keep in your wardrobe reflect the general climate where you live. In a cold climate, you own thick coats; in a warm climate, you own more light shirts.

Second, think of weather as your mood and climate as your personality. Your mood can change hour by hour, just like weather. Your personality is more stable and shows over months and years, just like climate. Neither analogy is perfect, but both give a friendly way to remember the difference.

If you remember only one thing, remember: outfit = weather, wardrobe = climate.

How Climate Change Affects Weather

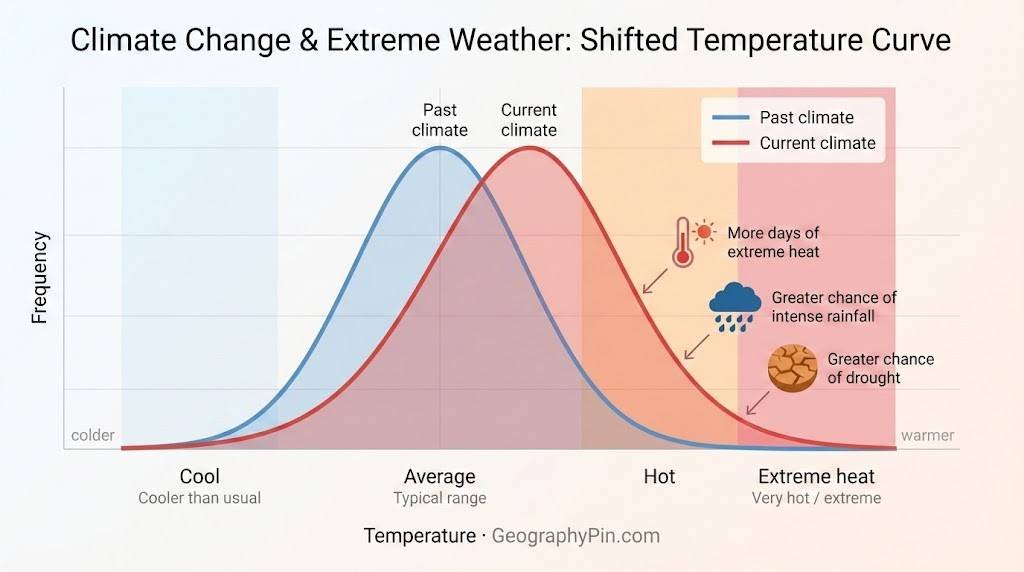

Climate change means the long-term warming and shifting of Earth’s climate due to rising greenhouse gas levels, mainly from burning fossil fuels and changing land use.

As of 2024, global surface temperatures are roughly 2.0°F (about 1.1°C) warmer on average than in the late 1800s. This may sound small, but it has big effects on weather patterns.

A warmer climate loads extra energy and moisture into the atmosphere. This can lead to more frequent or intense heatwaves, heavier downpours, and, in some regions, longer dry spells. For instance, a storm that once produced 2 inches (about 50 millimeters) of rain in a day might now have conditions to produce 3 inches (about 75 millimeters) or more, increasing flood risk.

Climate change does not create every single storm or drought from nothing. Instead, it shifts the background conditions. Think of it as raising the height of a basketball court floor by a few inches. Players (weather systems) are the same, but they are now closer to the rim, so slam-dunks (extreme events) become easier and more common. In simple terms, climate change makes certain extreme weather events more likely and sometimes more intense.

When you hear people say “You cannot blame one storm on climate change,” they are talking about single events. Scientists now use “attribution studies” to estimate how climate change has increased the chance or strength of particular events, such as a heatwave that shattered records by 10°F (about 5.5°C) over large areas.

FAQ

Why do scientists use 30 years to define climate?

Scientists use at least 30 years to define climate so that short-term ups and downs do not dominate the picture. One very cold winter or one very hot summer can be unusual. A 30-year period smooths out these spikes and gives a stable view of averages and typical extremes. The key idea is that long records, not single years, define climate.

Can a place have strange weather but the same climate?

Yes. A place can experience an odd week or month, such as a snowy April or a cool summer, without its climate changing. Climate is about long-term patterns. One unusual season does not rewrite the climate record on its own. Only repeated changes over many years show a real climate shift.

Is climate change the same as global warming?

Global warming refers mainly to the rise in Earth’s average surface temperature. Climate change is broader. It includes warming, but also changes in rainfall patterns, snow and ice cover, sea level, storm intensity, and many other aspects of the climate system. The key idea is that climate change covers all the ways the long-term climate is shifting, not just temperature.

Can we feel climate change in daily weather?

We do not feel climate change as a single event. Instead, we notice patterns: more record-breaking hot days, fewer very cold nights, heavier downpours, or longer fire seasons. Each day’s weather is still changeable, but the statistics of many days begin to shift. The takeaway is that climate change shows up in trends, not in one day’s forecast.

Who studies weather and climate, and how can I learn more?

Meteorologists study weather, while climatologists study climate. Both fields draw on physics, math, and computer science. To learn more, you can follow national weather services, climate science organizations, and educational websites that explain new findings in clear language. Whenever possible, rely on national weather services and major science bodies rather than random social media posts.

What Did We Learn Today?

- Weather is short-term atmospheric conditions, while climate is the long-term pattern of those conditions.

- Both weather and climate share the same ingredients but differ in time scale and space scale.

- Meteorology focuses on daily forecasts; climatology focuses on decades of data and trends.

- Everyday analogies, like outfit vs wardrobe, make the difference easier to remember.

- Climate change is shifting climate patterns and loading the dice toward more extreme weather.